12 Things to Know About How the Latest Landfill Disposal Study Stacks Up

A new report which estimates that Americans are disposing of more than double the amount of waste in landfills than data estimated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is in step with the recent Environmental Research and Education Foundation (EREF) study, the group’s president says.

The latest study, authored by academics from Yale University and the University of Florida, aimed to analyze current landfill gas collection with regard to potential landfill methane emissions, according to a report published in Nature Climate Change Journal. The study was compiled by Jon Powell and Julie Zimmerman of Yale University and Timothy Townsend of University of Florida.

The Yale study supports the EREF report on recycling discussed earlier this month at the Waste360 Recycling Summit, which stated that both the amount of waste generated and the tonnage of recyclables processed is significantly higher than estimates by the EPA.

The Yale study supports the EREF report on recycling discussed earlier this month at the Waste360 Recycling Summit, which stated that both the amount of waste generated and the tonnage of recyclables processed is significantly higher than estimates by the EPA.

Bryan Staley, president and CEO of Raleigh, N.C.-based EREF, also says in an interview that Biocycle’s most recent State of Garbage report further corroborates the disparities from the traditional EPA data.

“All three data sets in essence show that the EPA grossly underestimates landfill tonnage and overall waste generation in general,” he says.

Here are 12 things to know about the report.

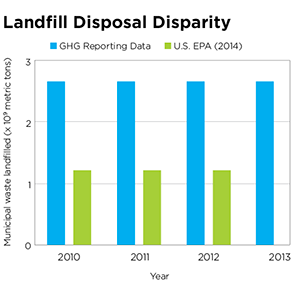

This study concludes that Americans disposed of 262 million metric tons of waste in landfills during 2012, compared with the EPA’s estimate of 122 million metric tons.

Those figures exceed the World Bank’s projected municipal waste generation rate for the United States in 2025 of 256 million metric tons by about 4 percent.

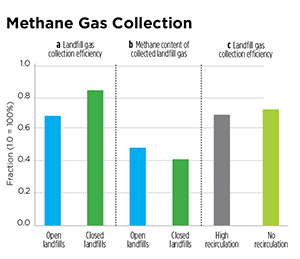

More than 1,200 municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills, both open and closed were analyzed. Gas collection systems at closed landfills were 17 percent more efficient than those at open landfills, but open landfills represented 91 percent of all landfill methane emission reductions. “These results demonstrate the clear need to target open landfills to achieve significant near-term methane emission reductions,” the report stated.

Methane content collected at open landfills was richer, 48.5 percent, compared with that collected at closed landfills, 41.1 percent.

One challenge to improving landfill gas collection is concern about aggressive systems prompting landfill fires.

The disposal figures actually are likely to be underestimates, because the data was culled from the EPA’s GHG (greenhouse gas) Reporting Rule, and smaller landfills are not required to report. The study estimates an additional 10 million to 36 million metric tons of waste were disposed of in 2011.

The average disposal rate increased 0.3 percent annually from 2010 to 2013, adding about 2.7 years of disposal capacity each year. Landfills in the United States have a median of 34 years of capacity remaining, according to the report.

Conclusion from the study: “Thus, on the basis of growth in disposal rates and indications of continued reliance on landfilling as a waste management method, capturing LFG (landfill gas) generated and reducing these emissions must be a target to meet stated reduction goals in the waste sector.”

The EREF study in comparison covers about 1,600 landfills, including smaller landfills not covered by the GHG rule. The EREF study did correct for construction and demolition (C&D) waste in its study, while the Yale study did not, so the fact that EREF’s tonnage is lower is not surprising, Staley says.

The Yale study data was facility based–a bottom-up approach as opposed to the EPA’s top-down method. “We have substantial corroboration from multiple independent lines of research showing that a top-down methodology is just not accurate,” Staley says.

Staley says the fact that the Yale study noted that landfill gas collection efficiencies were higher at closed landfills versus open landfills is not surprising. “Certainly a closed landfill is going to have a higher gas collection efficiency because you no longer have a working phase.”

The EREF president questioned the Yale study’s points about the risk of landfill fires. “Basically the way I read that: ‘We don’t understand anything about why fires occur, but therefore we should plan for it.’ It makes no sense,” Staley says. “I found that to be a particularly weak part of the paper.”

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)