A Lot to Digest: The State of Anaerobic Digestion

While composting gets most of the attention, anaerobic digestion is gaining as a means of diverting organic waste and generating valuable energy besides.

For advocates of anaerobic digestion (AD), the process of breaking down organic waste with bacteria and the absence of oxygen, is a relatively untapped waste management method that’s a breath of fresh air.

It is widely popular in Germany, which many consider the most advanced country in the world when it comes to renewable energy. Germany is the fourth largest generator of wind energy, but it would take three times that much wind power to match the energy the nation produces with AD, says Paul Sellew, CEO of Harvest Power in Waltham, Mass. Moreover, AD plants, being baseload generation, operate constantly and aren’t subject to the unpredictability of nature.

"It doesn't get the attention of wind and solar," he says. “[AD plants] generate much higher quality renewable energy and are therefore more reliable to the grid.”

There are two types of AD: wet, or “low solid,” and dry, or “high solid.” The wet process typically is used in wastewater treatment plants, says Emily Hanson, community relations manager for GreenWaste Recovery Inc. of San Jose, Calif., a sister company with Zanker Road Resource Management Ltd. In the wet process the material needs to be in a milkshake-like slurry with a lot of water added.

There are two types of AD: wet, or “low solid,” and dry, or “high solid.” The wet process typically is used in wastewater treatment plants, says Emily Hanson, community relations manager for GreenWaste Recovery Inc. of San Jose, Calif., a sister company with Zanker Road Resource Management Ltd. In the wet process the material needs to be in a milkshake-like slurry with a lot of water added.

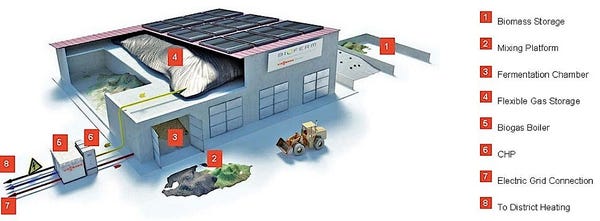

Bioferm Energy Systems of Madison, Wis., is the U.S. unit of a German firm and an AD technology provider. Bioferm uses both the wet and dry processes. So far the wet method has been more widely used, but not because it’s better — just different, says Gabriella Huerta, marketing & public relations for Bioferm. “It depends on what you want to put into your digestion,” she says.

Manure processing, for example, is more suited to a wet fermentation process because of its high liquid content. Yard wastes also work well with the wet method, says Huerta.

Food waste, she says, has been typically better suited for the dry option, with dry substrates that won’t leak out. Sellew, whose company also employs both methods, mixes food and yard waste together in the dry process but uses food waste and more liquid waste for the wet means.

GreenWaste through its new subsidiary Zero Waste Energy Development Co. LLC (where Hanson is project manager) currently is developing the first commercial-scale AD dry fermentation project in the United States, a facility in San Jose that eventually will be capable of processing 270,000 tons annually. The facility should be operational in late 2013.

GreenWaste and Zanker have been collecting and composting organics. “We were looking for an opportunity to capture the energy value in addition to just creating compost,” Hanson says. At full capacity the facility should produce 5.1 megawatts of electricity.

“We chose a dry fermentation system because in California water is a precious resource and we don’t have to add a lot of front energy to derive energy on the back end,” Hanson says.

Wetting an Appetite

One successful example of the wet process is the wastewaster treatment plant in Oakland, Calif., owned and operated by the East Bay Municipal Utility District. In 2003 the district started using its excess capacity by taking in food waste and producing digester gas through AD, says Donald Gray, supervisor of process engineering & information systems.

The district now operates 11 digesters, each with a capacity of 2 million gallons. Ultimately it could process 200-300 tons per day.

Some of the food waste needs pretreatment before going to the digester because it’s too dry or has contaminants, so the district developed its own process for that material. But the district also partnered with San Francisco-based Recology Inc., which handles some of the pretreatment. In addition, the district works with Phoenix-based Republic Services Inc.’s Allied Waste unit. “For us it’s essential there’s a link between us and the hauler when it comes to food waste,” Gray says. “And it’s a nice option for haulers to recycle this material teaming with wastewater treatment plants.”

The generation of energy from AD is big advantage for the process, advocates say. “Instead of consuming oxygen to stabilize these organic acids it’s converted to usable energy, which composting can’t do,” Gray says. Hauler partners also can use the energy, though conversion to compressed natural gas (CNG) or liquid natural gas (LNG), to fuel and no renewable energy policy it doesn’t make sense,” he says. “But if you have the policy and higher disposal costs it makes sense. You have to pick your spots; it’s not one size fits all.”

Coast to Coast

Because of the disposal cost issues, Sellew has found AD to be a strong option on both coasts in North America, typically focusing more on major population centers. How far away the landfill is can be part of that equation. “Market conditions really dictate the viability of this approach,” he says.

Low energy prices can make an AD project a tougher sell, because the payback will take longer, Huerta adds.

Like many waste and recycling enterprises, getting sited and permitted can be among the biggest challenges for AD projects, Hanson says – particularly in California. ”Finding and selecting their trucks.

There is less of an odor problem with AD using an enclosed system. Gray says AD provides a nice synergy with composters for that reason, and also because the anaerobically digested food waste is more stable, takes less time to break down and is a great feedstock. And it can be used directly for land applications.

There is less of an odor problem with AD using an enclosed system. Gray says AD provides a nice synergy with composters for that reason, and also because the anaerobically digested food waste is more stable, takes less time to break down and is a great feedstock. And it can be used directly for land applications.

For wastewater treatment plants with excess capacity, like East Bay’s, “it’s a low-cost method with little or no capital needed and no additional land,” says Gray.

Sellew says while AD provides a lot of advantages, its suitability depends on the situation. “If you have low-cost landfills and permitting is a huge challenge.” Because the San Jose project is the first of its kind, regulators don’t have other points of reference to draw on. “Facility regulators haven’t known what to do,” she says. “They’ve been trying to shoehorn us into existing regulations.” But as they understood the project better, they worked to expand permits to include facility operations and feedstock issues. And it should become easier for subsequent facilities once the San Jose model is in place, according to Hanson.

Zero Waste Energy has a 15-year organic feedstock processing agreement with the city of San Jose. “You need the guaranteed revenue,” Hanson says. “You can’t just look at the technology because nobody will finance it without a guaranteed revenue source.”

When pursuing an AD project concerns also can arise about fire and human safety, because methane is being created in an enclosed facility.

Since there is the need to pump the material when using wet digesters, Gray says, an added preprocessing step must be taken to get rid of contaminants.

Agriculture continues to be a popular customer for AD projects to handle the manure and food waste generated there. Huerta adds that agricultural waste can also be a fertilizer and energy source for the farms. But Sellew says his best customers are often corporate managers, “looking for cost-effective outlets that promote organics sustainability.” Also, as more mandates emerge to divert waste from landfills, he sees municipalities becoming more interested.

Universities have become unforeseen partners. Bioferm has joined with the University of Wisconsin in Oshkosh to create a dry fermentation plant that’s also become something of a living lab, Huerta says. It’s a way for students to learn how to reduce their carbon footprint and see an attractive waste management option.

Fermenting the Future

When speculating about the growth of AD, Sellew likens it to yard waste 15 years ago. Governments began passing bans on yard waste or mandating recycling of the material, and that helped jumpstart composting. “I look at food waste being now where yard waste was 15 years ago. You see the beginning of the infrastructure buildup.”

He believes it will start slowly, demonstrate viability, and establish reference facilities and a strong balance sheet – “All the things required to do business with municipalities. When you see these working models, that when it will begin to ramp up.”

He believes it will start slowly, demonstrate viability, and establish reference facilities and a strong balance sheet – “All the things required to do business with municipalities. When you see these working models, that when it will begin to ramp up.”

The market potential is huge. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2010 estimated food and yard waste in the United States at 65 million tons, with an additional 10 million to 15 million tons in Canada.

Federal policy in Germany has helped that nation operate more than 1,000 AD facilities. Huerta adds, “In Germany organics are seen as a source of energy. We (in the United States) view it as waste management.”

A key in America is that now food waste increasingly is being separated. “We need to establish the model,” Sellew says. “We’re right at the beginning of this trend in North America.”

But unlike Germany, it won’t be federal policy that drives AD in the future. He’s certain it instead will be pushed by states. Massachusetts for example is one state that’s been aggressive regarding organics.

It also will come from corporate sustainability efforts. “You can’t underestimate how that’s driving diversion from landfill to alternative methods,” Sellew says.

Those advocating zero waste need to determine what to do with organics, Hanson says. There’s composting and AD, and she argues that AD is more appealing because of the energy value. “Anaerobic digestion and composting are the two proven technologies globally as ways to handle organics from the municipal solid waste (MSW) stream,” adds Sellew.

AD’s popularity is definitely starting to take off in the Midwest, Huerta says. “In Wisconsin there’s huge biogas potential, particularly in dairy farms.”

East Bay was the first wastewater treatment plant in the United States to take in food waste, Gray says, but now many more are, and haulers are increasingly interested in partnering with them as a way to reuse the food waste.

With aggressive recycling goals such as California’s 75-percent diversion target, AD projects should grow in popularity, Gray says. “One of the areas that seems relatively untapped is organics, so this is a great opportunity for recycling, especially with wastewater treatment plants being typically close to the source. It’s a nice fit.”

To wit, in 2010 Americans generated 34.76 million tons of food waste, or 13.9 percent of total MSW, according to the EPA. Of that total, just 2.8 percent, or 970,000 tons, were composted.

Hanson says when commercial facilities like the Zero Waste Energy San Jose project come on board, the great potential of the market, the technology and the interest should offer significant growth potential for AD.

But Sellew cautions that the technology will have to be adapted for a given market. “We’re not Germany,” he says.

Allan Gerlat is News Editor for Waste Age and waste360.com.

About the Author

You May Also Like