Cold Fire

A new landfill-gas-to-energy project in Alaska pushes the climate boundary for this technology.

Alaska is called the last frontier, and that designation could apply to landfill gas-to-energy projects as well. The state’s first such project will open later this year in Anchorage. It could be the state’s last as well. But it’s a project that met the challenge of Alaska’s unique climate and demographics.

The city of Anchorage opened its landfill in 1987 and had long been flaring the gas, although it built a gas collection system in 2006. The city’s engineers had been working on the idea of converting the gas for some time, says Paul Alcantar, Anchorage’s director of solid waste services. It was particularly the brainchild of Mark Madden, the city’s former solid waste director and now manager of planning and engineering. But it had practical beginnings.

“We were needing to start collecting to be in compliance with NSPS (new source performance standard) regulations,” Madden says. “But we recognized it was a valuable resource.”

The city put out a request for proposals (RFP). At first, “we weren’t totally sold that electricity was the number one choice, but we were open to it,” Madden says.

The biggest challenge for the project was its general financial viability, agrees Dan Gavora, president and CEO of Fairbanks, Alaska-based Doyon Utilities LLC, which won the contract. “Everybody talks green but in today’s environment it’s all about the budget. So there was a lot of skepticism.”

But turning waste to energy proved to be the obvious choice. “The economics were way better with this alternative,” Madden says.

Doyon built and owns the power plant, and built and operates the gas processing facility for Anchorage. Madden says Doyon moved quickly; the firm only got the go-ahead a year ago. The project now is in a test phase and should be ready to go in late November.

Green Meets Olive Drab

A big factor in the equation is the primary customer for the gas, the joint Army-Air Force base Elmendorf-Richardson, which is next to the landfill and hosts part of the landfill gas-to-energy (LFGTE) facility on its property. The base also saw the value in the project. It had a strong need to secure a reliable energy source and a mandate to employ a certain amount of green energy. Those factors were key to making the project happen, Gavora says.

“The army didn’t have the wherewithal to get it done,” he says. But the military ended up paying for much of the project, whose economic efficiencies made it additionally attractive. Doyon has had a contract with the base for years to privatize many of the base’s utilities.

It’s also important for the military to be able support the local community in times of crisis, Gavora says, so this project works into that need as well. “Anchorage just had a weather event where the whole city went dark. We were able to island ourselves and bring the post back on from the landfill generation.”

Early projections of power generation have worked out for the base. “We met the military’s renewable energy goals by 700 percent, so we’re pretty ecstatic,” Gavora says.

Cooking with Methane and Natural Gas

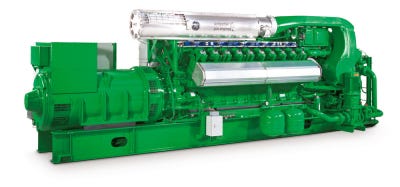

The Fairfield, Conn.-based General Electric Co. also became involved in the project by designing and supplying the Jenbacher gas engines for the plant. The key feature of the engines for the Anchorage operation is that they can run on both landfill and natural gas and don’t require mixing tanks, says Steve Hall from Philadelphia-based Western Energy Systems, GE’s North America distributor for the product.

The engines can handle both fuels as long as the companies plan for that up front, says Scott Nolen, product line management leader for power generation for GE Gas Engines.

The engines can handle both fuels as long as the companies plan for that up front, says Scott Nolen, product line management leader for power generation for GE Gas Engines.

Officials expect the project to grow. It currently has four units operating and will be adding a fifth within a year. Gavora says it could add a sixth unit within five years.

Each unit generates 1.4 megawatts. If a sixth unit comes on eventually, the ultimate generation should be 8.2 megawatts, Madden says.

The Anchorage landfill is now at 38 percent of its total capacity of about 40 million cubic yards. It should be able to accept waste until 2050, Madden says. Based on the modeling that officials did, production should peak when they reach capacity. The LFGTE project should have 60 to 70 years of total life.

Alaskan LFGTE Tundra

The Anchorage landfill is generating a fairly robust amount of methane, Gavora says. It is by far the biggest landfill in Alaska, and likely the only one with promising LFGTE potential. The next largest landfill is in Fairbanks and is only one-third the size of the Anchorage facility. And the climate in that northern Alaska city is significantly different than that of southern Anchorage.

“You need a certain amount of biological activity for the gas to produce,” he says. “Currently there’s not much methane [in Fairbanks] at all because of the extreme conditions. I don’t even think they have a flare requirement.”

While all of Alaska is cold, Anchorage has more of a maritime climate so the temperature lows are not as intense, Gavora says. Nevertheless, the cold poses challenges in just about every aspect of operations at the Alaska project. “A big deal for us is operating the pipelines and removing moisture,” Gavora says. “There’s a lot of liquid in it when the gas comes out. You have the cold temperatures and it has to be treated and conditioned before it’s sent down the pipeline to the generation facility. It’s more of a hurdle.”

Hall says that the pipeline was specially designed so the moisture wouldn’t freeze. It’s a two-part process: extracting as much liquid as possible and then removing what condensate does form.

For the engines the extreme weather is something that GE is used to. “The Anchorage temperatures are not that much different than northern Europe sites that we’ve done, such as Moscow,” Nolen says. GE installed engines for a much colder Alaskan climate in Prudhoe Bay. In Anchorage the engines operate inside the facility’s buildings, although generally with ambient temperatures.

Coming In From the Cold

Before the project began, substantial work had to be done with the soil on the site. The quality was poor and swampy, and it had to be reinforced, Hall says.

Those kinds of conditions permeated all aspects of the project. “It’s part of the general operation in more of an arctic environment that affects pretty much everything we do,” Gavora says.

Those kinds of conditions permeated all aspects of the project. “It’s part of the general operation in more of an arctic environment that affects pretty much everything we do,” Gavora says.

Doyon pays Anchorage for the gas, which gives the city “a fairly nice revenue source for the future development of the landfill,” Madden says. The solid waste operation is required to generate revenue to cover all its costs. And while he says the revenue could fluctuate dramatically with the flux of the market, the city is hoping to see $1 million to $2 million annually from the project.

“If we can receive revenue from the gas and stabilize our costs, that’s a win-win,” Alcantar says.

Madden says the city is happy with how the project is turning out. Officials checked with other cold-weather cities to get a better sense of what they could expect. “Logistics in Anchorage are a lot more challenging than other places,” he says. “It’s not that it’s so cold here, but our winters are very long. We were really concerned on how that would affect the gas model and collection.”

And temperatures frequently do fall below zero. Madden says the city buried some trash in a landfill cell and found it still frozen two years later.

Despite the adverse conditions, the Anchorage project so far has outpaced expectations: “We found, if anything, we underestimated how much gas it’d produce,” says Madden.

Still, he admits, it’s not your walk-in-the-park LFGTE operation. “It’s a little slower process here than what you’d see in southern California.”

Allan Gerlat is News Editor for Waste Age and waste360.com.

About the Author

You May Also Like