New Observations on PFAS from GWMS

In this month’s edition of Business Insights, we offer new observations on PFAS gleaned from two sessions at GWMS.

In this edition of Business Insights, we offer new observations on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that we gleaned from attending two sessions dedicated to PFAS at Global Waste Management Symposium (GWMS), which was held in Indian Wells, Calif., from February 23 to 26. This is intended to be a follow-on to our summary primer on PFAS in the January 2020 Business Insights, and it is likely to be the second of a number of pieces on this evolving issue for the solid waste industry.

More Color on PFAS: Sources and Effects

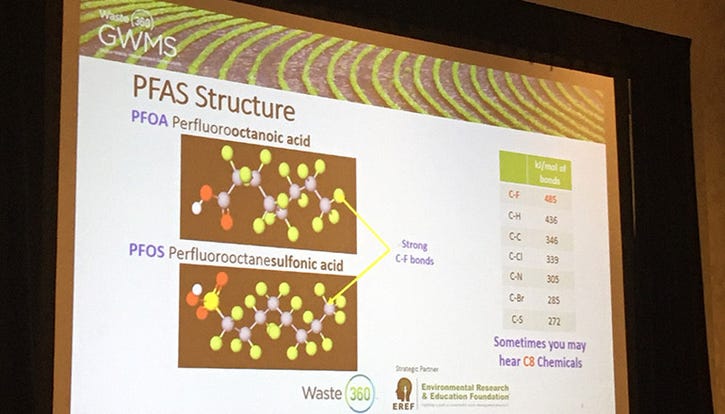

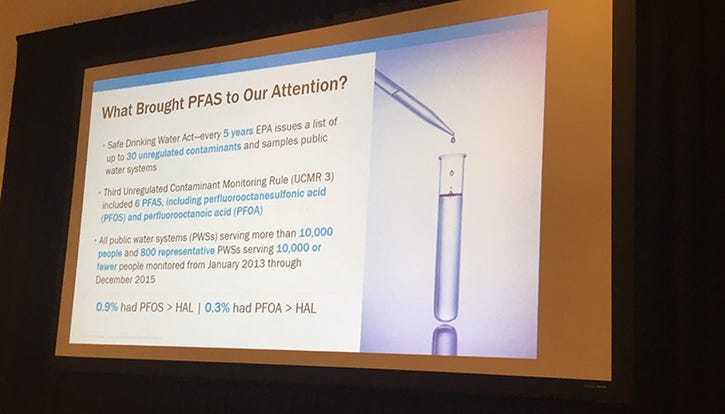

Although the current regulatory focus is generally on drinking water, it was apparent from Brown and Caldwell’s Laura Carpenter’s presentation that arguably more PFAS is ingested through diet in particular (some of the ramifications of which will be discussed later) and likely through air and dust sources as well. On the positive side, however, it was pointed out that the so-called “longer-chain” (or C-F 6-8) PFAS, which include perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), remain in the bloodstream much longer, potentially six to eight years, while the “shorter-chain” PFAS (C-F 4 or lower) pass through and out of the bloodstream in a couple of weeks. PFOA and PFOS have been identified with negative health effects and are generally considered most dangerous, and they are no longer manufactured in the U.S., although they are still found in drinking water sources and landfill leachate, given past widespread use. The shorter-chain PFAS are those generally manufactured and in use today.

Regulatory and Legal Impetus

It was made very clear from conference participants that fear and politics are driving state-led regulatory efforts, and the associated science and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidance is far behind. That said, no one had any great hope that regulations were likely to be rolled back, even if future scientific findings were to support that. There are now 26 states that are eyeing or have implemented some type of PFAS regulation. Generally, the focus is on drinking water sources and standards, publicly-owned treatment works (POTWs) and landfill leachate, roughly in that order. Obviously, none of these are generators of PFAS, but they are intermediaries or points of concentration. As such, they are considered “point sources” and are likely to be regulated because it’s easier—the actual sources (everything from food packaging, to carpets, to rain gear) are just too diffuse to effectively regulate. Thus, it was noted by several participants that landfills (more specifically landfill leachate) were likely to be regulatory targets, at least in some states—as is the case in California and Vermont, for example. Thus, it is important for landfill owners to be part of the dialogue—by pointing out that landfills are not the problem but part of the solution, as landfills can contain PFAS given their sophisticated engineering, as noted by luncheon speaker Michael E. Hoffman, managing director and group head of diversified industrials at Stifel.

Kevin Torrens, also of Brown and Caldwell, noted that probably 90 percent of PFAS remains sequestered within the landfill. That said, PFAS generators (3M and DuPont come up most often, though there are others) are not coming through the rise of this issue unscathed—lawsuits and legal actions are increasingly targeting them to pay for the cleanup of contaminated wells and sites. Right now, under the EPA’s PFAS Action Plan, there is no plan to declare PFAS (in general) as hazardous, which would put them under the purview of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). That is likely a positive for the solid waste industry—although CERCLA would pull in the generators as potentially responsible parties and put them on the hook for funding cleanups, CERCLA also has a tendency to pull anyone involved into a bureaucratic and regulatory dragnet.

Treatment Methods Discussed

Several presentations within the two sessions delved into treatment options and methods, both in use and emerging. In what is admittedly a generalization, three technologies were most often noted as currently in use and widely field-tested—granular activated carbon (GAC) filtration, ion exchange and reverse osmosis. It should be noted, however, that all three are removal (filtration), not destruction, technologies—the PFAS-containing residue must still be reactivated under high temperatures, disposed/contained or destroyed (incinerated). All three technologies were considered largely effective, with GAC and ion exchange cited as less expensive, while reverse osmosis was characterized as more costly, but with higher efficacy.

It was also noted several times that these technologies were most effective for longer-chain PFAS, which would be assumed to be a positive, as they are considered the most dangerous. However, most of the studies done on these technologies involved “clean water” (drinking water sources). It was noted by several somewhat frustrated conference participants that landfill leachate is a whole different breed, in terms of “dirtiness” and the variety of chemical compounds it potentially contains—many of which are site specific. It was acknowledged that all three technologies may require onsite pretreatment, if not multistage or tertiary treatment, when it comes to dealing with PFAS in landfill leachate. Several conference participants, but notably HTX Solutions, offer an onsite, several-stage treatment specifically for landfill leachate. A number of emerging or developmental technologies were also discussed, but again, most were being tested on clean water.

Of note, the topics/solutions of recirculation (putting the leachate collected back in the landfill) and deep well injection also arose. Recirculation serves the purpose of keeping the PFAS contained, given the landfill’s liner system. Deep well injection was at one time in wide use for disposing of hazardous waste, but it was noted that the permitting process can be long and costly, even in states where it is still permitted.

Cost Remains a Big Question

Historically, leachate treatment (mostly through POTWs as more than 60 percent of landfill leachate is discharged to POTWs) cost a few pennies per gallon, but given trends of the last few years, leachate treatment costs are now estimated to be in the area of mid-single digit cents per gallon, which admittedly averages a wide range. Including more widespread PFAS treatment, three presenters variously put the potential leachate treatment operating costs at 4 to 18, 13 to 15 and 12 to 18 cents per gallon, respectively, while the cost to destroy PFAS residue via incineration was put at $2 per gallon. Industry presenters shied away from identifying or estimating capital costs. Several noted it is too site specific to give a good average, given that pre-treatment or even multistage treatment may be necessary. Also, several consultants said they were bound by confidentiality or non-disclosure agreements with regard to divulging cost details.

Other Looming Complexities, but Also Potential Opportunities

As previously noted, although much of the regulatory focus is currently on drinking water and drinking water standards, there are several other potential ramifications for the solid waste industry. First, there is increasing concern about PFAS in composting, given the frequent use of PFAS in food packaging, which is frequently accepted at compost sites if it is considered biodegradable.

Secondly, if and when PFAS at POTWs is increasingly scrutinized, it could have repercussions on the land spreading of biosolids—a common use for sewage sludge. Both of these issues factor into PFAS ingestion from diet. Several conference presenters noted the need for cooperation and coordination between POTWs and landfill owners, as there is often a co-dependency between the two—the POTW for treating leachate and the landfill for accepting sewage sludge. This, and other landfilling or containment of PFAS remediation residues, could be potential opportunities for the solid waste industry.

Leone Young is the principal of LTY ERC, LLC, providing consulting and research services to, and conducting special projects for, the environmental services industry, primarily the solid waste sector.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)