GWMS 2020: Stifel’s Hoffman Highlights Hot Topics in Waste

Key topics of interest from Michael E. Hoffman’s discussion included safety, the shift from private to publicly-traded companies, PFAS, landfill capacity and more.

Michael E. Hoffman, managing director and group head of diversified industrials at Stifel, challenged Global Waste Management Symposium (GWMS) attendees on Tuesday to join him in a mission to remove the industry from its position as one of the top 10 most dangerous occupations in North America.

In addition, with the recent breaking news that GFL Environmental intends to relaunch its initial public offering, a key topic of interest from Hoffman’s discussion was the shift from private to publicly-traded companies and the wave of consolidation in the garbage business.

During Tuesday’s lunch, Hoffman also highlighted Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG); landfill leachate and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS); and a landfill capacity outlook.

Safety Challenge: “Out of 10 in 10”

Waste and recycling is one of the most dangerous industries in North America. Hoffman asked GWMS attendees how the industry can move out of the top 10 in 10 most dangerous industries for workers.

Industry fatalities have risen, while national numbers have declined. In solid waste, the major culprit is transportation. And while the national average for work-related transportation fatalities is 41 percent, the waste and recycling industry lies within the 60 percent range.

“We can do something about this. There is a data-based solution to this,” stressed Hoffman. “I don’t think that we are collecting or sharing enough data that would help. Way too many employees don’t make it home in this business, and you are in control of this as engineers. This is a data-driven issue.”

“Let’s move this needle over the next 10 years and get us out of top 10 in 10 if we can,” he urged.

Going Private to Public in the Garbage Business

When Hoffman began his career 32 years ago, he said a small company would get started and friends and family would help initially with funding to get things going. Then, the company would get to a critical position with capital markets and go public. And at some point, maybe the company would sell.

Now, since 2010, businesses still start with friends and family and private capital, and then the private capital sells to private capital, explained Hoffman. Then, after an interchange of private capital to private capital, the business eventually goes public.

“I think GFL is now going to go public. I can’t confirm that, but I think they will,” he said. “But there is a very good chance that if there weren’t public capital markets for them to come into, they would have just kept going back to private equity. This is an extraordinary example in our garbage industry.”

GFL has grown to USD$3 billion, or C$4 billion, and roughly USD$900 million, or C$1.115 billion, in EBITDA.

“So, it’s a big company, highly profitable and highly levered (6.5 times levered),” explained Hoffman. “But they’ve done that all initially with friends and family and then all private capital. They changed hands on a private capital standpoint three times in the last 14 years and managed to get to this size.”

This happened because private equity is willing to run a more concentrated vote, which means the company only has 10 or 15 investments, and asset managers tend to have 150 stocks in their fund, explained Hoffman.

“There’s no way one person can know what’s happening with all 150 names. So, you end up regressing your returns as a result,” said Hoffman.

“And the public asset manager does not tolerate leverage. If the public capital markets don’t wake up to this, there is a great risk we will be disintermediated. But it is a risk that is coming that you can’t ignore and will influence the growth of businesses long term,” he added.

Hoffman also noted that he thinks public markets will figure out a balance and will find a way to tolerate more risk. And embracing stakeholders and shareholders must blend together to generate above-average returns, he added.

“You can, in fact, provide the data that makes you an extraordinarily attractive investment, both public and private, because of the things that you’re doing at the end of the day that are sustainable, that hit ESG and that do have impact because you’re doing things that not only impact employees but that impact the customers, the vendors and the communities you live in,” Hoffman told GWMS attendees.

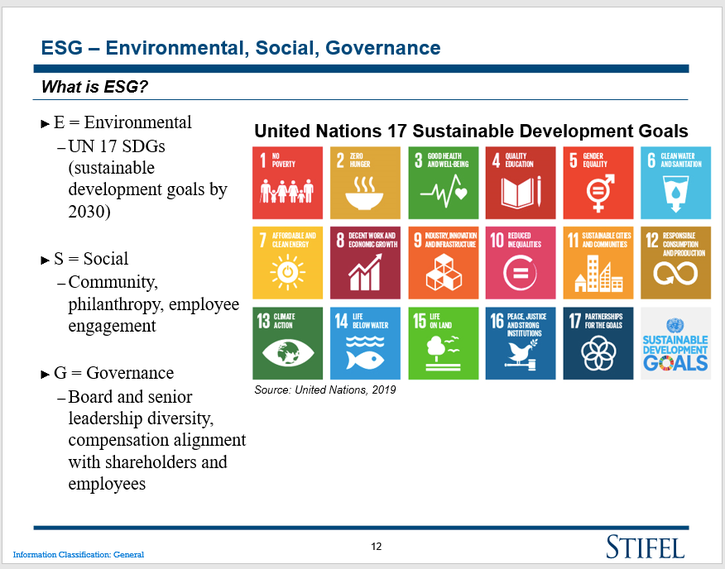

Environmental, Social, Governance

There is no question that the world is looking at all businesses through a different lens. The reality is that conversations at work and at home will increasingly involve people talking about environmental sustainability.

Governance is something that corporate America has been taking the lead on in terms of diversity in leadership and training.

“I’ve attended this conference five times, and the diversity in this room is dramatic from what it was 10 years ago. So, this is out there. You need to figure out how to own it,” said Hoffman.

American businesses are figuring out how to run parallel with both shareholders and stakeholders. Stakeholders comprise employees, customers, vendors and the communities people live and operate in. And the waste industry is part of the solution, not the problem, when it comes to matters like PFAS and methane.

PFAS and Leachate

It’s no surprise that the industry has a PFAS issue. And roughly 40 billion gallons of leachate a year come out of about 4,000 active and inactive landfills.

“In that leachate, we are clearly concentrating PFAS, and here’s the issue I will share with you. You are a point of concentration. You are not a generator, and you know that. But it makes you an easy target for a regulator or a politician to turn and say, ‘As a point of concentration, I am going to put the onus on you.’

Hoffman urged attendees to own this subject and to take the lead in resolving the problem.

“I think I can say this safely: In 25 years since Subtitle D, we have never had a catastrophic failure on a Subtitle D-designed landfill. Yes, I know, we’ve had slides. But there has never been a major leak.”

“These are extraordinarily sophisticated engineering projects,” he added. “You can own this as a solution to this problem. If we need to sequester it, it’s the perfect place to do it. If we need to treat it, you’re also one of the world’s most sophisticated managers of complex industrial liquids. You have an expertise that is unrivaled. There is an enormous opportunity here that we have yet to fully tap into.”

Landfill Gas and Capacity

Solid waste landfills generate 10.5 million to 11.5 million megawatt hours from landfill gas—mostly methane. The majority is sold as baseload power to the grid, which has been done for decades.

“Until five years ago, we generated less solar than we had done for the last 20 years with landfill gas,” said Hoffman. “We are selling this as baseload power to the grid. Baseload means guaranteeing that you will fill the grid.”

“It’s high-power renewable energy,” he added. “More importantly, it’s the most effective bioreactor I know.”

He added that landfill and waste-to-energy is the only way to do this right now. And in the U.S, waste-to-energy has stalled amid diminishing landfill capacity.

About 20 years ago, there were nearly 2,500 landfills, while 25 years ago, there were almost 5,000, Hoffman pointed out. Smaller landfills have been closing, and there are about 20 companies that account for 75 to 80 percent of air space today.

The U.S. has 1,269 nonhazardous waste landfills with about half controlled by 25 companies. Over the next 10 years, Hoffman said he thinks total nonhazardous waste landfills (Subtitle D) will be down to 900 to 1,100.

“The bigger issue here is that within that concentration is a lot more tension on the ones that are left. And you need to start talking about the extraordinary complexity and sophistication in the engineering,” Hoffman told GWMS attendees. “In civil engineering, there is a landfill class because this is so complicated. Embrace it. Let people understand how well designed they are because they are. I think they are more sophisticated than dams and that’s a pretty powerful engineering project that holds that much water back for that long. So, learn how to talk about it and embrace it.”

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)