Maine Ends Land Application of PFAS-Impregnated Sludge and Pushes EPA to Follow Suit

Maine is leading efforts to address PFAS contamination from sludge applied to farmland, becoming the first state to ban the practice and committing significant resources to support affected farmers. As the state pushes for federal action, it continues to uncover widespread contamination.

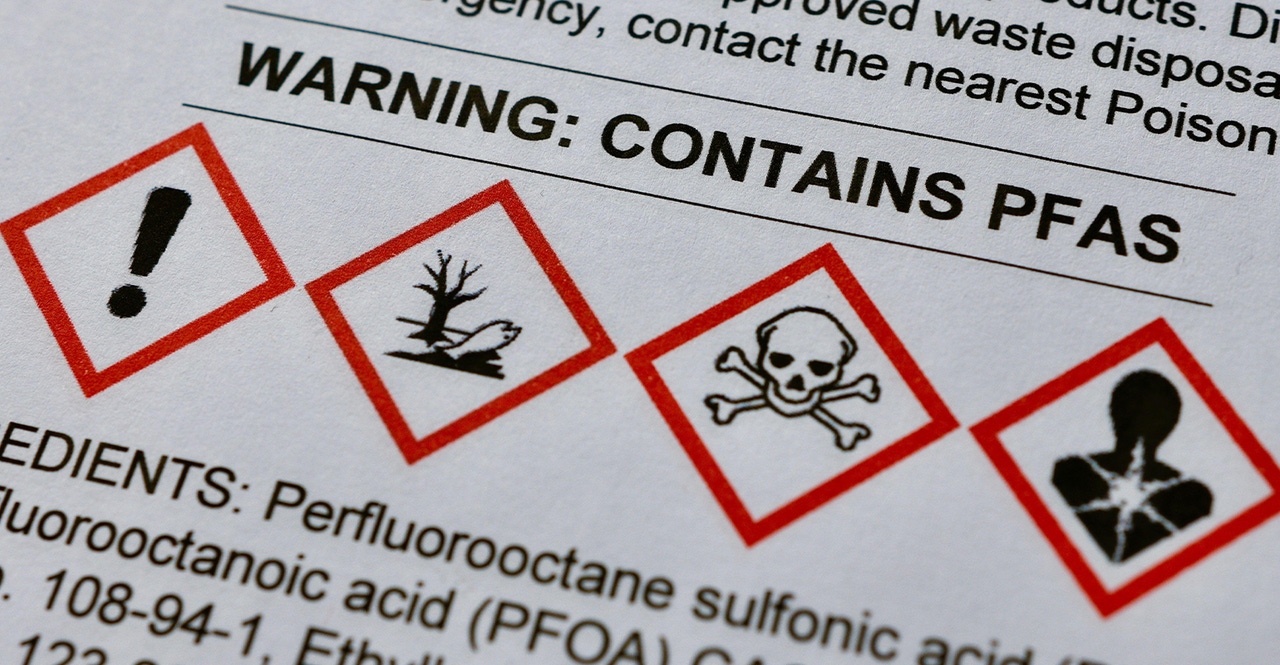

For decades, U.S. farmers have applied sludge to their land, believing they were doing something good for their property and for their community. They were providing wastewater treatment plants an alternative to costly sewage disposal, while getting ahold of what was assumed to be a safe, cheap fertilizer. But the premise that this practice is a win for both farmers and wastewater plants—and ultimately the environment—has been turned on its head as states increasingly find the sludge to be laden with PFAS. This reality is hitting some farmers hard.

Maine is leading the way in work to rid farms and surrounding communities of these toxic chemicals found in tens of thousands of consumers products that ultimately make their way into sewer systems and sludge.

Maine is the first state to ban land application of this material. It is actively testing for PFAS in soil and water; has set PFAS concentration limits in milk sourced from dairy farms; and committed over $100M to tackle PFAS contamination, 60 percent of which is dedicated solely to supporting impacted farmers. Now the state is pushing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to step in.

“In the absence of federal action, Maine has undertaken numerous initiatives to understand the extent of PFAS contamination and protect its residents from exposure. These efforts are rooted in Maine’s commitment to the wellbeing of its citizens and vibrancy of its communities, and is emblematic of the State motto, Dirigo, ‘I lead,’” says Beth Valentine, director of Maine’s PFAS Fund.

The state began vetting potential risk of PFAS-loaded sludge not too long after learning one of its dairy farms was impacted by these contaminants, back in 2016. Still, it was thought that this might be one isolated incident. But over the next few years more information came to light suggesting otherwise.

Maine’s Department of Agriculture and Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) had done preliminary testing, including of milk sold at the retail level, and ultimately traced high PFOS concentrations to two dairy operations. So began a deeper dive into the likely extent of PFAS contamination in the region’s soil and water. Maine’s DEP started looking at sites where sludge had been land applied as questions around this practice arose and began testing for contamination.

One of the earliest operations found to have high PFAS levels was an organic farm, which came as somewhat of a surprise as farms with organic certification do not land apply sludge, says Sarah Alexander, executive director of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA). The nonprofit, which advocates for legislation to support organic farming, began working with the state to determine where the problems lie and soon realized there were many ways PFAS from sludge could make its way onto these agricultural lands.

The true magnitude of Maine’s troubles became clearer when the state published a map of sites with permits to land apply sludge and also disclosed water, soil, and wildlife testing results.

“Farms started to see themselves on the map that did not realize they had an issue, including organic farms who were not aware that sludge was spread years before they bought their property. These are forever chemicals. They were still in the water and soil and contaminating their production,” Alexander says.

PFAS was even showing up on farms where sludge was never land applied. These compounds can move through water and soil, so rural communities were experiencing a ripple effect, with PFAS-impregnated soil traveling across properties, and sometimes infiltrating neighboring water wells.

The investigations and subsequent cleanup projects have extended to residential water supplies, with the state footing the bill for filtration systems, both for farms and to protect household drinking wells.

The DEP and Department of Agriculture are continuing to survey farms that were issued permits to spread sludge, recently completing two tiers in a four-tier project. So far they have confirmed that 68 farms have had at least one soil or water sample demonstrating contamination levels warranting increased evaluation of the farm’s overall management strategies and products to determine if and how that resource may be safely utilized for agricultural production, Valentine says.

To date, the consequences of these forever chemicals have forced five farms out of business.

The state’s PFAS fund provides monies for financial and technical assistance; is leveraged to buy out PFAS-contaminated land; to fund academic research; and for blood testing and mental health services for farmers.

In addition, a PFAS response program set up to keep struggling businesses afloat has allocated over $3.3M for income replacement, farm infrastructure, water filtration, and compensation for lost livestock.

Maine State Senator Stacy Brenner, a farmer herself, co-chairs the PFAS fund.

Her position is that the state sanctioned land application of biosolids, and thus has a responsibility to help impacted farmers through this crisis.

“The goal is to provide the support farmers have stated they need to be whole after being confronted with the reality of contamination,” she says, commenting that the fund was intentionally designed to be farmer driven.

“Their insights have informed the policy and implementation. When you know better you do better,” Brenner says.

Land application of residuals, including sludge, is a widespread practice across the U.S. and remains an approved method by the U.S. EPA.

Aiming to change that status, MOFGA is suing the agency, along with Johnson County, Texas whose farmers are also feeling the consequences of PFAS from sludge spreading. The plaintiffs argue that the EPA is not following requirements under the Clean Water Act.

Alexander says at least 18 PFAS are known to “regularly” show up in sludge that the EPA has not added to its list of toxins to be regulated in accordance with the law.

“We know this is an important national issue. Maine is not alone. We just happen to be looking for the problem and addressing it in a holistic way. I think the reality is when communities look for this, they will find it,” Alexander says.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)