Minnesota Months Away from Sweeping PFAS Ban

This crackdown follows Minnesota’s prohibition of the compounds in food packaging (which goes beyond the Food and Drug Administration’s recently imposed restrictions). A few other states have done the same and, like the North Star State, have gone on to outlaw these persistent chemicals in other products. But Minnesota’s Amara’s Law is the most sweeping in scope in that it goes after whole categories of goods, rather than only individual products.

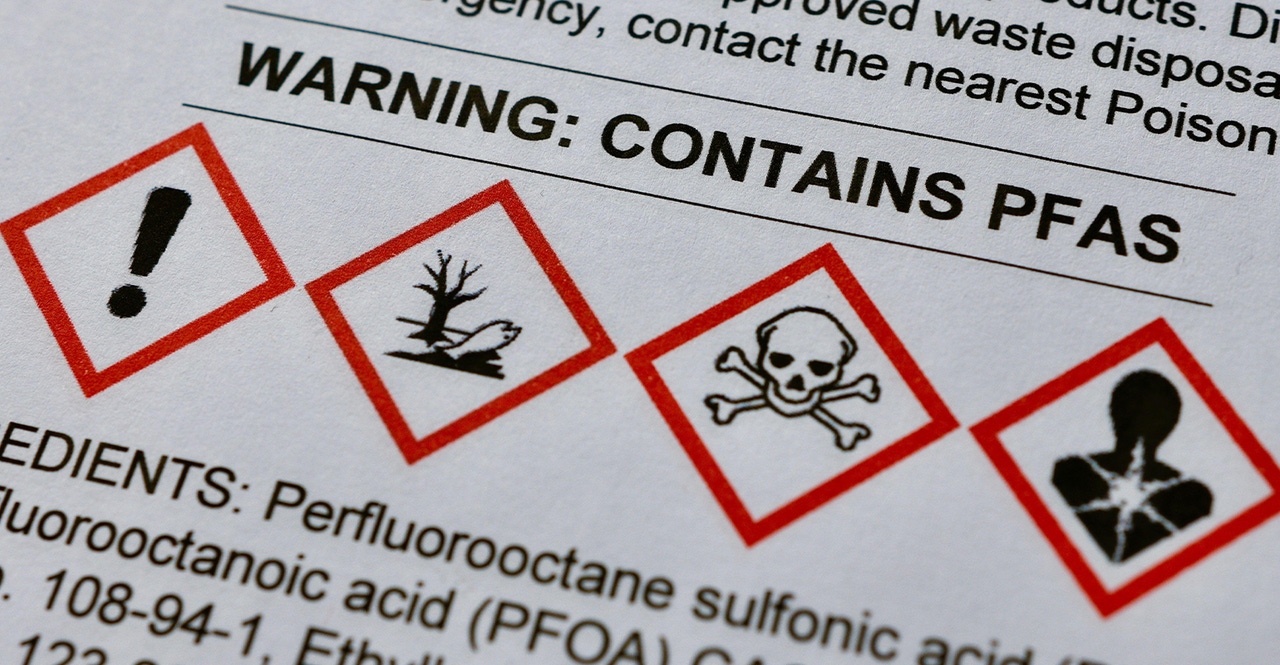

Minnesota has passed what environmental and public health advocates call the country’s toughest regulations around per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). The state is banning the use of these toxic manmade chemicals in 11 consumer product categories in January 2025; then prohibiting PFAS in all products by 2032 unless they get a “currently unavoidable use” exemption.

This crackdown follows Minnesota’s prohibition of the compounds in food packaging (which goes beyond the Food and Drug Administration’s recently imposed restrictions). A few other states have done the same and, like the North Star State, have gone on to outlaw these persistent chemicals in other products. But Minnesota’s Amara’s Law is the most sweeping in scope in that it goes after whole categories of goods, rather than only individual products.

The 11 categories targeted in the first wave of regulations are those with direct exposure risks and or that can perform adequately without PFAS, with a few being dental floss, cookware, cosmetics, and menstrual products.

Manufacturers adding PFAS to other goods must report on its use beginning in 2026.

“Through our reporting requirements we will be looking for product descriptions, PFAS types and amounts, as well as their function. That data will help us understand and determine where it is critical and where we can get rid of it, or where we can find an alternative,” says Andria Kurbondski, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) PFAS pollution prevention lead.

Over time, the chemicals have shown up in multiple media, from different sources, and in various state locations.

The investigations date back to 2002. That’s when MPCA found the compounds in groundwater in the eastern suburbs near 3M facilities and disposal sites.

Much later, in-depth testing (unrelated to the 3M/eastern suburbs scenario) uncovered PFAS in groundwater at 100 of 102 closed landfills across the state.

The contaminants came from materials disposed of over many years, underscoring the importance of understanding products’ life cycle and their potential long-term impacts, says Adam Olson, public affairs and engagement strategist, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

“It’s not just preventing exposure risk that could come from direct use, but also the risk of environmental contamination decades after PFAS-containing products or packages are thrown away, be it through incineration, landfilling, or recycling streams,” Olson says.

These toxins have also made their way into Minnesotans’ drinking water, resulting in a $850M settlement in 2018 with 3M, who was allegedly responsible for the contamination. The impacted communities, concentrated in the East Metro region, are still working on drinking water treatment systems to tackle the “forever chemicals.”

It’s not an isolated problem in the east. PFAS has seeped into water supplies throughout the state, not unlike in other regions. Currently, Minnesota is focusing on about 18 communities that require treatment to meet federal drinking water requirements. It is estimated that getting supplies up to standards will cost over $1B. That includes investigation, treatment systems, and remediation and does not account for what the state has already spent, Olson says.

“If we could interrupt PFAS in wastewater streams, before it enters drinking water, it would go a long way in protecting the environment and trying to get ahead of this problem,” he says.

MPCA commissioned a report to figure out what would be entailed in removing and destroying PFAS from wastewater.

“We learned it is unaffordable. In our state alone it would cost between $14B and $28B over 20 years,” Olson says.

That’s in large part why the policy focus has turned to stopping PFAS at the generation source, as Amara’s Law intends to do. In the works for some time, the regulation is named for a 20-year-old Minnesotan who fought hard for rigorous PFAS rules. Amara Strande lived in one of the highly impacted communities and died weeks before the law passed of cancer believed to be related to her exposure.

Manufacturers have had questions about what Amara’s Law will mean for them. Concluding whether a specific product should be regulated is not always straightforward.

“We sometimes have to do more research to know the answer. We look closely at our legal definitions in the statute to determine if a product falls under a given category. And we are doing a lot of engagement to make clarifications,” Kurbondski says.

MPCA has issued guidance statements on its website for the 2025 prohibitions. The agency posts updated lists and webinars, including responses to businesses’ inquiries made during Q&A sessions.

Kurbondski anticipates that manufacturers’ reporting data, which will be publicly available, will not only help inform decisions on what else to regulate in Minnesota but help other states that are homing in on PFAS. And there are plenty of them increasing their scrutiny.

At least eight states introduced bills in the past year to eliminate PFAS in some consumer products. Among them are Colorado, Connecticut, and Vermont whose legislation has since been signed into law.

Kate Donovan, director of northeast environmental health for Natural Resources Defense Council, along with her colleagues, is advocating for such bills in New York and California and has been involved in advising Minnesota on rulemaking for Amara’s Law.

Minnesota’s approach—moving toward an outright ban on all product categories deemed as nonessential—is where policy needs to go, Donovan says.

The reason it’s so important in her view is that PFAS is very widely used yet hidden. Not only is it intentionally added to products for functionality, but it also ends up in goods via manufacturing processes such as to make nonstick molds or to treat yarns for weavability.

“Yet, it’s not on labels nor is it regularly tested for. So, we need to make assessments to figure out where it is, whether it’s needed or not, and move to safer alternatives,” Donovan attests.

“We need to focus on the low-hanging fruit—consumer products where we know there are safer alternatives. After that, we need to push for Minnesota-style bills that actually address all nonessential PFAS use across product sectors and across manufacturing and industrial uses,” she says.

Kurbondski is optimistic about what Minnesota’s work, and that of other states coming on board, could mean down the road as industry sees expectations heightening.

“Our hope is that more [manufacturers] will get on the bandwagon and say, ‘We do not need it; what else can we use?’”

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)