Takeaways from Waste Management’s 2019 Sustainability Forum

The forum addressed the world’s worsening plastics pollution crisis.

This year’s Waste Management Sustainability Forum illuminated what has been called the greatest global crisis of our time: the ocean plastics pollution problem.

“It is a huge, worldwide issue how our human activities are impacting our rivers, streams and oceans,” said Jim Fish, president and CEO of Waste Management.

“Managing the plastics in the waste stream is the next big challenge,” he added. “This issue isn’t a new problem, but it is an escalating one, and it hit the radar stream in a really big way in 2018. As the use of plastics has increased across the globe, the plastic pollution in the oceans has grown at an alarming rate. National Geographic’s June issue titled “Planet or Plastic?” identified plastic in marine environment as one of our greatest global challenges.”

The “2019 Waste Management Sustainability Forum: Big Ideas. Bold Action. Better World.” took place during the Phoenix Open golf tournament in Scottsdale, Ariz. This is the seventh year the tournament has been zero waste and the ninth annual sustainability forum for Waste Management.

Here are some key highlights from this year’s forum.

“Why Plastics? Why Now?”

Valerie Craig, deputy to the chief scientist and vice president of Impact Initiatives for National Geographic Society, kicked off her discussion with the following question: “Plastic: miracle material or environmental scourge?”

“Maybe both,” she said. “It is undeniable that [plastic] has changed our lives for the better. But it has also created a pollution problem at an almost unimaginable scale. It’s a problem that’s visible; we know it’s harmful, it’s global, but it’s also solvable.”

About 40 percent of the plastic that we use today is used just once before it’s tossed, explained Craig. Today, nearly 9 million tons of plastic enter the oceans every single year.

From the mid-1950s to now, explained Craig, we’ve produced about 8 billion metric tons of plastic, with nearly half of it produced in the last 15 years. At the rate we’re going, we’re set to hit 34 billion tons by 2050, she added.

The biggest market for plastics today is packaging materials. Craig noted that these items have an average use time of less than six months and often much less. Packaging materials are also the same items that are more than half of the waste of plastic produced today—whether it is disposed of correctly or not. Today, about half of the production of plastic products is happening in Asia. And China alone represents 29 percent of all plastics production.

Craig stressed that one of the biggest challenges associated with plastics today is how lightweight they are.

“It allows the problematic plastics like films and bags to be carried in the water and by the wind to where it doesn’t belong,” she explained. “But there is a trick to that, because it’s lightweight is what makes it so incredible. Picture thousands of glass bottles being carted around by truck or by airplane and now imagine that same number of bottles made from plastic. There is a wild weight difference between the glass bottles and the plastic bottles. And when it comes to transportation, that weight difference is a difference in carbon emissions. In a world where we have to be considering our impact on climate, what are we supposed to do with that? The bottom line is it’s not just as simple as saying let’s go back to where we were. We have to be thinking about the whole picture of all the materials we use—glass, plastic, aluminum, you name it—from its very early moments when it’s coming out of the ground as a raw material all the way to end of life.”

And once plastic waste ends up in the ocean, it breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces but never disappears. Instead, microplastics and nanoplastics are created that then end up permeating our environment and food chain. Additionally, once plastics are in the ocean, they’re nearly impossible to recover.

So, how can we solve this problem? Craig suggests working backwards through the value chain to see where we can take action to make sure zero waste ends up in the ocean. Craig turned the focus to materials design and waste management.

“For the general consumer on the street, they’re saying, ‘Why can’t it all just be biodegradable? Why can’t it all just be compostable?’” noted Craig. “When it comes to biodegradability, it starts with really just breaking down plastic into smaller and smaller pieces. But it’s really not environmentally benign. At the end, we are getting down to those smaller plastics again. True biodegradability is possible. It’s happening. These products are being produced, but they are just not yet at the scale to a large market.

However, she said the important thing to think about is determining what those truly flawed plastic items are that we need to keep out of the environment. Items such as thin films and plastic bags might be the items to focus on when it comes to biodegradables.

And when it comes to compostable plastics, Craig emphasized that it’s a viable option moving forward; however, “it is not necessarily applicable for everything, but for a lot of single-use plastics it is,” she said.

But for plastics, composting has to happen under specific conditions and under extremely high heat. That’s where industrial composting facilities come in.

“At the end of the day, it’s still a design issue and it’s still a waste management issue,” noted Craig. “They have to be tied together.”

“There are more simple solutions when it comes to design that we can do today,” she added. “Really small actions, such as things like considering the glues that we use that hold a wrapper around a bottle and the colors that we use. Minor changes can increase the recyclability for many of these products.”

Craig referred to granola bar and energy bar wrappers as her posterchild for a terrible product right now. In most cases, she explained, these wrappers are made with many kinds of different materials layered together, making them impossible to recycle.

“And once you layer a bunch of different materials together, what are you going to do with it? It’s nearly impossible to do anything with than landfill,” she stressed. “So, we can focus on reducing the number of materials that go into some of these packaging products and can we bring together the companies that are producing consumer products and get them to agree on a fewer set of options. Once we have a limited number of options, it’s a lot easier to invest in the correct infrastructure to deal with the waste of what those could be.”

How Waste has Become a Design Flaw

Dr. Leyla Acaroglu, a designer and sociologist, began her career as an industrial designer and ended up uncovering the fact that most of the things that we have designed in our lives are designed without much consideration for the user or the global world. Throughout her daily work, Acaroglu studies ways we can re-interact with our everyday products in a different way.

“Design is the most powerful force that humans have created,” she explained. “We designed the entire world to meet our needs. We design the world and the world designs us. Ultimately, every single person on this planet is an investor of the future based on the actions that they take today.”

“Design is also a system,” added Acaroglu. “When we talk about ocean plastic waste, that is the product of design. It’s not that someone sat there and evilly conspired destroy the ocean—I hope that was not the case. There were these series of actions and events that came together at a specific point in time, and now we have a global tragedy in our oceans that we are all equally responsible for.”

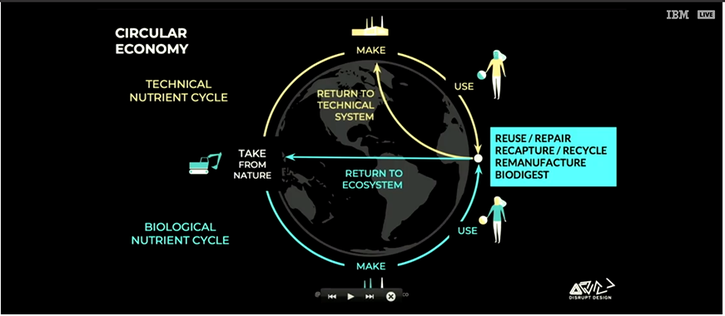

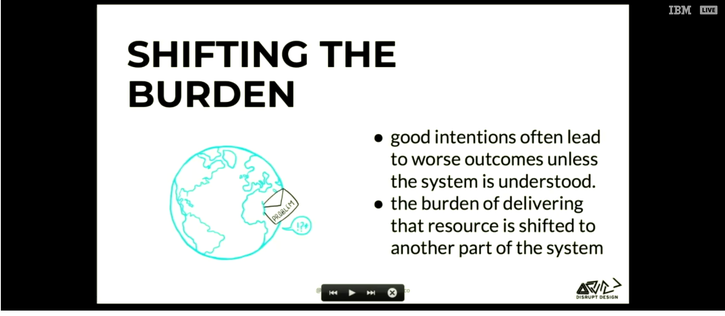

The problem has emerged due to the linear economic systems we’ve created. That means we take resources from nature, transfer them to the industrial systems that we use to create goods and then we landfill those goods—or sometimes they leak into nature and sometimes we burn them.

“This linear system is wasteful and it’s really inefficient,” she said. “The proposition to solve the linear economy is a circular economy. We have created a system where things are valueless. They have single purpose, they are used up and then they are no longer valued. When they are no longer valued, no one takes responsibility for them. When you have a circular economy, from a business standpoint it asks, ‘how do we revalue things from the get-go?’”

A circular economy means reimagining the functionality of what is delivered to the market, the economy and the human need. That’s how we revolutionize the way design out the problem from the start, Acaroglu pointed out.

“Waste is our design flaw; it’s a problem that someone created,” she emphasized. “We live in a system of reinforcing the problem over finding a new solution. Waste is translated as a loss. The whole concept of a single-use product is that it will have the minimal amount of functional value that you could possibly attribute to it. From a social perspective, what it teaches us is that we all have participated in the normalization of the waste-based culture.”

Acaroglu suggested businesses and individuals conduct waste audits or assessments to see where the problems are in their systems. She also stressed the importance of accountability and the willingness to change. Moving forward, she urged companies to redesign products and services to be put back into the system to help mitigate the problem created over the past few generations.

Recycling Update from Waste Management

Brent Bell is the vice president of Waste Management Recycling Services, and the moment he knew recycling was in trouble in 2018 had nothing to do with China. It was a night he was having dinner with his mother.

Bell regularly audits his mother’s recycling cart at her home and she’s well aware that’s his routine. But one night at the dinner table, she asked him if she could put Christmas lights in her recycling bin.

“That’s the moment I realized recycling was in trouble,” Bell quipped. “I also realized that my mom is a wishcycler. For those of you who don’t know, there are millions of Americans who have this problem. Wishcycling is a term we use to describe folks who have the best intentions—they want to put everything they can in their recycling carts with hopes that it actually does get recycled. Wishcycling today is the leading cause of contamination in the U.S. Our contamination level is around 25 percent in our programs.”

Contaminants can impact good recycling programs by increasing the cost, reducing efficiencies of the operations and lowering commodity values. But the most serious problem many companies have with contamination is the dangers it causes the employees who sort recyclables, noted Bell.

And over the years, Bell and the employees at Waste Management have seen some odd items in the recycling stream.

“Propane cylinders and batteries do not belong in recycling bins,” he stressed. “And neither do plastic bags, bowling balls, garden hoses, chains and grenade launchers—yes, we get grenades, too. We get deer, but that’s seasonal, we even found a black bear and a python snake.”

What Bell has found most fascinating is the number of bowling balls that Waste Management has received. Every week, the company collects 100 bowling balls in its recycling facilities—that’s more than 5,000 bowling balls a year and it works out to be 80,000 pounds of bowling balls annually.

“The last I checked, bowling balls aren’t on anybody’s acceptable lists for recycling programs, but somehow, once a week, we get 100 wishcyclers who decide, ‘I am going to take my 16-pound bowling ball and go to my recycling cart and just drop it in,’” said Bell.

Waste Management also sees 96,000 propane tanks every year in the recycling stream, as well as 28,000 batteries every month. The company spends 140,000 hours a year cleaning screens at its facilities, noted Bell.

He said the number one question customers ask is what they can do to help. Bell explained that it’s all about cleaning up the contamination and knowing that not everything that has a number on it can be recycled in a curbside program.

Moving forward, he said Waste Management is investing more into public education, like tagging customers’ bins, and technology to help mitigate contamination in the stream. He also noted that 2018 was the first full year the company was able to collect data from a sorting robot at one of its recycling facilities. Bell added that additional screens, optical sorters and robotics will play an optimal role in the materials recovery facility cycle.

“Looking out to 2019, the markets don’t look much better than they did in 2018, but we are continuing to make advancements in technologies,” he said.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)