The Case for Compostables

How communities can use compostable products to unlock dramatic increases in landfill diversion and recycling rates.

January 22, 2013

Steven Mojo, Biodegradable Products Institute

Compostable products (polymers and fiber-based products that decompose safely in professionally managed composting operations) are transformative products that can make it possible to double or triple community landfill diversion and recycling rates. Rather than trying to sort out non-degradable plastics, waste generators are simply replacing plastics with compostable substitutes. No sorting, no screening at the composting facility and, most importantly, no contamination from non-degradable plastics. This, in turn, can make mixed organics composting much more efficient, unlocking dramatic increases in recycling and landfill diversion.

Have We Hit the “Recycling Limit”?

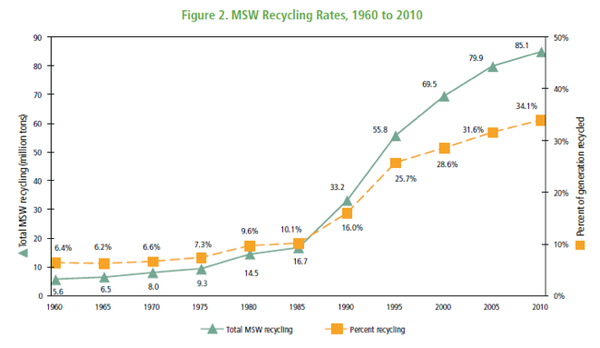

The chart above shows that the “Golden Era” of recycling rate increases has passed: recycling rates have only increased 10 points in the past 15 years. While it is fair to expect more growth in the overall recycling rate, unless states and communities undertake new initiatives, we can expect only modest incremental improvements in landfill diversion.

Recycling plays an important role in diverting packaging wastes from landfills. For example, of the 75 million tons of packaging generated in 2010, an impressive 48 percent was recovered. But the success of recycling is concentrated among a few, easy-to-recycle packages.

Part of the problem is that landfill diversion programs have focused on packaging but not what’s inside it. Comingled with household wastes is a lot of food: food processing residuals, grocery store trimmings and spoilage, and household scraps. Each year 33 million tons of food scraps are buried or burned in the United States, making it the single largest waste item the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency tracks. More food scraps are landfilled or incinerated each year than plastics or paperboard.

Once you remove the clean, easy-to-sort packages, you’re left with all of this food waste commingled with materials that are either too soiled or wet to be economically recycled: 25 million tons of wet, food-stained corrugated boxes, paper and plastic bags, boxes, towels and tissues, disposable plates and cups.

Worse, all this trash is predominantly putrescible (readily biodegradable under the appropriate conditions): paper, cardboard, food — all decomposing in an uncontrolled fashion in the landfills and creating methane, a greenhouse gas 21 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

In fact, landfills are responsible for 16 percent of U.S. methane emissions, behind natural gas and petroleum production, and so-called “cow burps.” As much as 30 percent of methane gas generated in landfills comes from discarded food, according to EPA. This unwanted decay also creates dangerous liquid leachate, which can damage local aquifers if not properly contained or treated.

Composting: Recycling's Next Frontier

Composting is undoubtedly the best solution to recycle this putrescible waste and keep it out of landfills. There are several advantages that make composting a solid environmental winner:

Proven technology. There are approximately 3,000 leaf and yard waste compost facilities operating in North America, while more than 200 compost facilities handle highly putrescible materials such as food waste.

Locally focused. Composting has favorable economics because organic waste can be composted conveniently (and locally) at existing community compost facilities rather than being trucked or barged hundreds of miles away to distant landfills or incinerators.

Sustainable. Good quality humus (composting’s end-product) is in high demand by organic gardeners, landscapers and arborists. It is an essential ingredient to healthy soil and healthy plants.

Almost 20 million tons of leaves and grass are composted today, nearly 60 percent of all such yard waste disposed annually according to EPA’s Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery. And composting achieved this rate of landfill diversion in less than 15 years between 1990 and 2005.

Composting is very successful at landfill diversion, but it is still underutilized relative to its potential. Sixty percent of yard waste is diverted from landfills, yet less than 3 percent of food scraps are composted. And there is evidence that major metropolitan areas experience a dramatic boost in recycling rates when they target mixed organics wastes, not just leaves and grass.

San Francisco, for example, diverts 77 percent of its waste from landfills in part due to a program that collects 600 tons of food waste and wet/soiled paper per day, according to the Wall Street Journal. Meanwhile, Portland, Ore., has curtailed household collection of “trash” to twice per month since adding food scraps and wet/soiled paper to municipal composting. Also according to the Journal, trash volumes going to Portland-area landfills dropped 40 percent in the first quarter of 2012.

The Rose Garden, home of the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers, implemented a compostables program in 2010 targeting food service and concession waste. The program replaced plastic disposable food service items with certified compostable alternatives. As a result, more than 100,000 tons of trash have been composted and diverted from landfills.

On the East Coast, the state of Vermont passed a law in 2012 (House Bill 485) requiring mandatory recycling and composting of food and organic waste, eventually banning those materials from landfills by 2020. The law took effect July 1, 2012, and initially targets large food waste generators in 2014. In 2012, the Massachusetts State Department of Environmental Production proposed a similar rule.

And in Canada, approximately 30 percent of households are involved in source-separated residential collection.

Dozens of large communities are embarking on mixed organics collection, achieving impressive results. But thousands more towns and cities could, but don’t. The reasons are varied: lack of awareness, lack of suitable composting sites and other logistical challenges, bureaucratic inertia, etc.

One important roadblock for mixed organics composting is skepticism and resistance from composters themselves about potential contamination from non-degradable plastic packaging.

Composting leaves and grass clippings is relatively easy: yard waste is clean and simple to process. And premium-quality humus from these operations fetches top dollar. These facts create financial incentives for communities to collect more organics and build more facilities. It is the very definition of a sustainable business model.

But composting household and institutional mixed organics waste is more challenging, due in part to potential contamination from non-degradable plastic packaging. Plastic fragments must be sorted or screened out, which costs extra time and money. And, since sorting and screening are not always effective, humus products contaminated with plastic pieces have low commercial value.

Higher costs and lower selling prices are the opposite of a sustainable business model, so fewer composters and communities are willing to take the risk.

Unlocking the Potential

Compostable products can be used to break this stalemate and allow hundreds more communities to double or triple recycling rates. Rather than trying to sort out non-degradable plastics, waste generators are simply replacing them with compostable substitutes: products that look and feel like plastics, yet completely and safely disintegrate in a commercially managed compost facility. No sorting, no screening at the composting facility and, most importantly, no contamination from non-degradable plastics.

Think about the waste stream from a food concession operation at football stadium, school or fast-food restaurant: large piles of food scraps, liquids and wet, soggy paper, all hopelessly comingled with small bits of plastic packaging: drink lids, straws, plastic cups and cutlery. 80 to 90 percent of this trash is rich, putrescible biodegradable feedstock that’s perfect for composting. 10 to 20 percent is non-degradable plastics, all but impossible to sort out. This small, non-degradable fraction causes all of the waste to be rejected by a smart composter.

Even an incinerator should not take food wastes, which consist of up to 90 percent water, because it lowers the energy value of the entire load.

However, by substituting compostable products for non-degradable plastics, the entire waste stream is now compatible with commercial composting. Compostable products degrade completely and fully, just like other organics. They don’t need to be pre-sorted or screened. They simply degrade along with everything else. As little as one pound of compostable products can enable 10 pounds of organic trash to avoid the landfill via composting. This concept has the potential to unlock huge diversion rates in thousands of communities.

Mixed organics composting (incorporating compostable products) becomes more practical and sustainable since it requires less sorting and screening, and makes humus that is more valuable. This, in turn, attracts more composters and more communities who want to compost mixed organics.

The Value of Certification

The vision of compostable products unlocking the true potential of mixed organics composting is powerful, however the reality has to be tempered with two real-world truths:

People are easily confused.

Some people cheat.

Compostable products look and feel just like plastic, tempting unscrupulous suppliers to substitute “phony degradables” (partially degradable products, such as polypropylene and starch) for the real thing. Even paper- or fiber-based products (which most people presume are compostable) often contain a thin coating of non-degradable plastic such as polyethylene.

If you’re a composter handling hundreds of tons of mixed organic trash, it’s a real challenge. Phony degradables only get discovered after months of composting, when the offender is long out of reach. So the composter is stuck trying to sift out plastic contaminants or selling low-value, contaminated product at a loss.

The real victims are the composters’ customers, who may be banned from sending future organic wastes to the compost facility due to a single instance of plastics contamination.

The solution to this problem is a quality standard for compostable products so buyers won’t get cheated into paying for phony products, and composters won’t get stuck sifting out non-degradable junk.

The Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI) was founded in 1999 as a product certification agency to establish trust between waste generators and composters. Similar product certification programs (DIN-CERTCO and Vinçotte) exist in Europe, and are based on equally tough standards.

The BPI requires members to test products to meet stringent standards for compostability: ASTM D6400 (for plastic products), or ASTM D6868 (for plastic-coated and fiber-based products). These standards have no tolerance for non-degradable plastics, heavy metals or other residuals that could harm the quality of humus.

BPI-certified products earn the right to use “The Compostable Logo,” a seal of assurance that lets consumers and composters know the products will be safe for composting.

As of today, more than 140 companies use the BPI Compostable Logo on approximately 2,000 consumer products including yard waste collection bags, food serviceware (plates, cups, cutlery, lids and straws), packaging inserts, and merchandise bags. BPI members are strong advocates of mixed organic composting, and support local community efforts to expand composting for more businesses and households.

Composting is an important yet underutilized recycling technology that is a proven, practical solution to predominately organic waste streams. But contamination from non-degradable plastic products makes mixed organics unsustainable, due to the high costs for sorting/screening out contaminants, and the low-value of compost humus that contains residual plastic waste.

To make mixed organics composting more sustainable, waste generators (institutions, businesses, and consumers) can substitute new-generation compostable products for non-degradable items. This allows predominantly organic waste streams to be safely composted at commercial facilities, diverting thousands of tons of waste from overburdened landfills.

Certification of compostable products establishes the necessary trust between waste generators and composters, so mixed organics composting can succeed.

Steven Mojo is executive director of the New York City-based Biodegradable Products Institute.

You May Also Like