What’s The Most Important Solution To Climate Change? Reduce Food Waste

On Earth Day, we take pause to wonder, “What’s the best thing I can do for the environment?” It’s a difficult question to answer, as the list of behaviors we should be practicing to help fight climate change grows ever longer. We practically have to design our whole lives around maximizing our sustainability–minding consumption of animal products, limiting air travel, and of course, keeping clear of plastic. As our society evolves beyond the I-can-do-whatever-I-want-as-long-as-I-don’t-drive-a-gas-guzzler attitude, we’re finding ways to integrate environmental stewardship into more facets of our lives.

Culturally, we’re finally seeing the complexity of our environmental problems and recognizing there’s no easy cure-all. But most people don’t dedicate their whole existence to fighting climate change, and they want to get the most bang for their buck. So what is the most important solution to climate change? The answer might surprise you: reduce food waste.

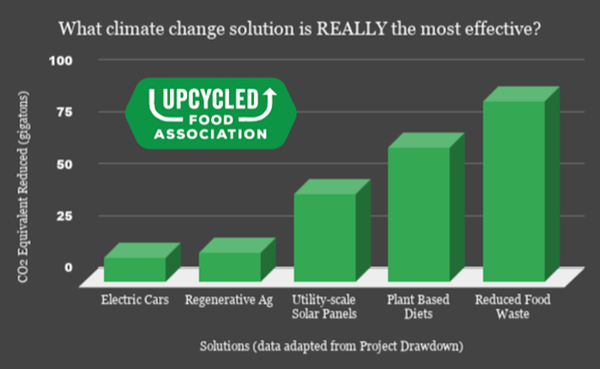

According to Project Drawdown, the global leader in quantifying climate change strategies, reducing food waste is the single greatest solution to bring climate-change-causing carbon out of the atmosphere and draw it down into the ground (where it belongs). The number one solution. Reducing food waste has the potential to draw 87 gigatons of CO2 out of the atmosphere, way ahead of a global plant-based diet (64 gigatons), electric cars (12 gigatons), regenerative agriculture (15 gigatons), even utility-scale solar panels (42 gigatons)! So when you say “sustainability,” why do most people still picture Impossible Burgers, solar panels, and Teslas? Sustainability, it turns out, is much more simple and cheaper to practice, and elegantly so.

The answer lies in a misunderstanding of two important systems, first where our food comes from, and second, where it goes.

Perhaps unexpectedly, where it goes is actually the simpler half, so we’ll deal with that first. Our search for the environmental silver bullet has effectively transformed the old adage “reduce, reuse, recycle,” into, incorrectly, “reduce, reduce, reduce.’ We harken to engrained images of devastated natural areas and overflowing landfills and revert to the most obvious knee-jerk solution–do less of that. And in the case of food waste, it really is important to do less.

Up to 40% of food produced for human consumption is wasted, adding up to billions of tons and hundreds of billions of dollars per year. It’s the single largest contributor to municipal landfills. And the greatest offender by sector? You and me.

More than restaurants, grocery stores, or farms themselves, the bulk of food rotting in landfills comes from your refrigerator, when you packed this week’s almond milk in front of last week’s tofu, only to rediscover it post-expiration date (a totally unreliable metric for healthful consumption, but that’s another topic). And once in the landfill, the food from your fridge releases methane–a lot of methane–which is a greenhouse gas much more powerful than CO2. So yes, if you want to help the environment, a great way to do it is to not let food that enters your home in a grocery bag (reusable, of course) leave in a trash bag (plastic, I presume).

In recap, reduce the amount of food you throw out. That’s pretty obvious. But if we want to live in the world that, well, we all want to live in, we have to do more than just reduce. We need to improve our food system, increasing the prevalence of the parts that work well.

Which brings us back to the first point. People don’t think about food waste when they think of sustainability because they don’t know where food comes from. Like a giant Rube Goldberg machine, every time you purchase food, whether it’s at a drive-thru or in a Whole Foods, there is a complex, global network that has conspired to make that exchange possible. We take for granted the land, labor, and energy it takes to grow, harvest, and transport the food we enjoy because we don’t understand what we can’t see.

The complexity and size of the behind-the-scenes work it takes to provide you and your seven billion closest friends with breakfast is hard to conceive, but here is a thought to put it in perspective: half of earth’s habitable land and 70% of its fresh water are used for agriculture. You may travel far and wide in your long life, but you will likely never visit the number of countries whose cumulative land areas equal the size of the world’s farms. To turn this immense landmass into our dinner, it takes trillions of dollars, and billions of people.

As big as this system is, it’s getting bigger. Agriculture is also the leading cause of deforestation, as trees and habitat are clearcut to make room for - in all likelihood - cows. This deforestation exacerbates environmental problems by reducing biodiversity and destroying CO2-consuming trees. When you buy something in the grocery store, you’re buying into its entire lifecycle.

It’s not that a big food system is necessarily bad. In fact, it might be a good thing our food economy is growing: we’re headed for a population of nine billion in a few short decades, and we can’t provide food for this increased population overnight. What’s wrong with this system is that it’s so inefficient. You wouldn’t buy a one acre property if you only got to use 0.6 acres of it, so why do we put up with farms that only profit from 60% of their capacity? (Globally, an area the size of China is used to grow food that is never eaten.) You wouldn’t buy 10 gallons of gas if you could only drive for six gallons worth, so why do we let our food distribution trucks carry so much food that won't be eaten? You wouldn’t buy a Vitamix that magically made 40% of your smoothie disappear, so why do we allow so many of the nutrients to go to waste as byproducts from our kitchens and manufacturing plants?

The problem isn’t that the food system is too big, it’s that we don’t put all the nutrients we’re creating to their highest and best use. There would be nothing wrong with putting most of our land and fresh water towards a healthy and sustainable food system. But putting most of our land and fresh water towards a food system that only kicks out 60% of the energy we put into it is, well, stupid.

So when you throw out a pound of bananas you never got around to making into banana bread, the impact on the environment is not only from the methane emitted from the bananas in the landfill. The true impact comes from: the deforestation of rainforest to make room for the corner of the farm that grows food that will never be eaten; the nutrients in the banana peel, which have value but no market; the semi truck hauling the portion of its load destined for the trash; and the grocery stores’ fluorescent lights shining down on to-be-wasted produce, gleaming with false hope to be consumed.

When you consider the whole lifecycle of food, it becomes possible to imagine the environmental impact of food waste. For every pound of food you throw into your trash (two large apples), imagine releasing two exercise ball-sized balloons of CO2 out your window (about two pounds of CO2). Then imagine you release two more balloons, then two more, everyday. Then imagine all your neighbors are doing the same. It’s this cumulative effect that allows global food waste to account for 8% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

So why do people picture electric cars, plant-based burgers, and solar panels when they picture sustainability? Because we are so disconnected from our food that we don’t realize how much energy goes into it; and therefore how much energy is wasted when food is not eaten.

It’s not only about reducing waste, it’s about increasing efficiency. What we need is a food system in which all food is elevated to its highest and best use as a normal practice. Understanding the life cycle of food is a start.

The beauty of food waste reduction as a strategy to address climate change is that virtually anyone can participate. How can you contribute to a food system in which all food goes to its highest and best use? Here are a few suggestions:

Don’t throw away food. This is easier to do when you buy less at a time. If you eat 100% of the food you buy, you’ll save more than one thousand bucks per year, the average amount we spend on food we end up tossing. At the very least, food should be composted, where nutrients are retained to turn healthy soil back into food.

Buy upcycled food. Upcycled foods are products made from the nutrients that would otherwise go to waste. This allows our food economy to grow without more strain on the environment. If 40% of food is going to waste, there’s a big economic opportunity to efficiently retain all those nutrients and turn them into the next generation of sustainable food.

Donate money to food rescue organizations. An important player in food waste reduction is the network of hundreds of food rescue organizations around the world, rescuing food that would otherwise go to waste and providing it to food insecure populations. The work these organizations do is critical, especially in times of uncertainty (e.g., global pandemic).

Don’t get me wrong. Just because it’s the most important solution doesn’t mean it’s the only solution. Eight percent of greenhouse gas emissions is significant, but if we completely eliminate food waste we’re still left with the other 92% to deal with. There’s still no silver bullet, but before you go spending $15,000 on solar panels or $100,000 on a Tesla, consider reducing your food waste first.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)