When a landfill’s life is over, the land’s life goes on. And when there’s a plan in place for the landfill site’s next use, the landfill operator is usually at the center of the sometimes-complicated effort to prepare the location for that purpose.

There’s an identified use for a landfill before closure in roughly half the cases, says William Schubert, Houston-based Waste Management Inc.’s senior director for the company’s closed sites management group. One of the most important points for future development, he says, is to not wait until the end to decide. “The earlier you can identify the end use the better off you are.”

For example, it’s easier to shape the landfill into the form needed as it is being built. “Trying to do it all with additional soil at the end of the job, you sometimes get settlement problems that make for more trouble,” he says.

Jeremy Morris, senior engineer with Geosyntec Consultants Inc. in Columbia, Md., has seen a trend toward more sustainable landfill closures, compatible with the surrounding terrain, a break from the traditional tendency to cap a landfill and walk away. “In a traditional Subtitle D closure your reuse options will be rather limited,” he says. “If you can move to a more sustainable type of approach you open up a broader range of reuse opportunities. And you should be able to reduce to amount of care needed because site is more compatible with surroundings.”

That long-range vision can involve not only the design of the closure system but also proactively trying to degrade the waste more than it might be in a traditional landfill. Morris advocates design that allows for a transition to passive landfill management, such as a gravity flow for leachate rather than pumping. “Basically you design control systems and envision end-use conditions that minimize the need to restrict land use,” he says.

That long-range vision can involve not only the design of the closure system but also proactively trying to degrade the waste more than it might be in a traditional landfill. Morris advocates design that allows for a transition to passive landfill management, such as a gravity flow for leachate rather than pumping. “Basically you design control systems and envision end-use conditions that minimize the need to restrict land use,” he says.

And sometimes the intended use of a landfill changes in the process. “It takes decades to finish some of these landfills,” Schubert says. “During that time the attitudes and needs of the public planning bodies changes.”

Teeing Off on Redevelopment

There’s no typical reuse for closed landfills, and each application has different design challenges. Golf courses were popular in the 1980s and 1990s but that market has hit hard times recently, Schubert says. When a golf course is the next use landfill operators can go so far as to plan the major fairways and bunkers when shaping the landfill, minimizing the amount of clean dirt needed to regrade.

There’s no typical reuse for closed landfills, and each application has different design challenges. Golf courses were popular in the 1980s and 1990s but that market has hit hard times recently, Schubert says. When a golf course is the next use landfill operators can go so far as to plan the major fairways and bunkers when shaping the landfill, minimizing the amount of clean dirt needed to regrade.

With golf courses you want to avoid over-irrigating, he adds, so Waste Management has taken the approach of planting high prairie grass and wildflowers on landfills to minimize the amount of watering needed. And a thick final cover is required to imbed irrigation systems.

Cross-country courses are a growing use, and landfills offer an advantage of the summit serving as a good vantage point for people to watch the race. Waste Management has done a lot of recreational facilities such as baseball diamonds and soccer fields. With those applications, you need enough grade to facilitate runoff, but it needs to be flat enough to play on, Schubert says. One old landfill became a BMX bike course where bumps and dips are actually assets, and Waste Management built the grade on top with that terrain.

Another landfill was turned into a wetlands area for habitat restoration. The region where the landfill developed included an old gravel pit area, and Schubert says the company was able to dam it up to create the wetlands, allowing an adequate buffer between that and the landfill.

Morris sees renewable energy projects as the most popular post-closure application recently. With renewable energy projects, it’s easy to restrict access and yet have a revenue-generating system in place. Wider public-access applications increase the need for control systems and cover-monitoring systems and raise concerns about possible exposure to gas and leachate.

“That’s probably the biggest barrier to opening up landfills to a wider range of reuses,” he says.

One example of the value of early landfill reuse planning was a landfill operator that sought approval of a vertical expansion to extend the landfill’s life. As part of the permitting process the operators plan to turn the landfill into a renewable energy park after closure, and they’ll put part of the revenue from the future tipping fees toward the eventual installation of wind turbines, solar panels, a geothermal heating system and other types of features.

“That’s something that would not have been considered ten years ago,” Morris says.

He suggests that the uses for a closed landfill site could evolve in tandem with the closure process. Post-closure care of a landfill usually covers 30 years. “Post-closure care would step down over time as the landfill stabilizes and the level of care needed reduces. Then the range of reuse options will increase.” It could progress from biocrops for fuels to livestock or a wildlife park to driving ranges and ballparks and eventually to full-access public parks.

A Fresh (Kills) Start

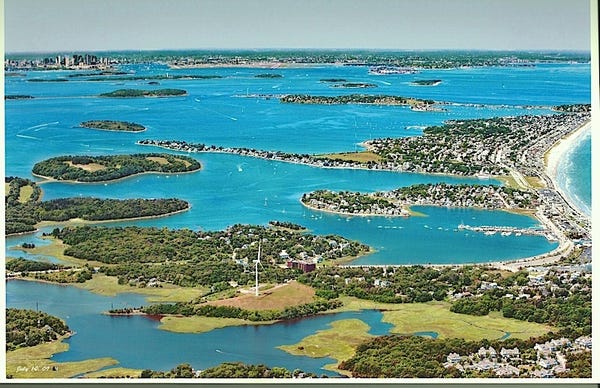

Morris cites as the best example of landfill reuse the evolution of New York City’s Fresh Kills landfill, once the largest landfill in the United States, now Freshkills Park, a 2,200-acre site that when completed will be offer public parkland three times the size of Central Park.

When the landfill closed in 2001, New York City civic leaders went to then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani and said, “ ‘We’ll never get this much vacant land again, so let’s have an international competition for the best and highest use for it,’ ” says Eloise Hirsh, Fresh Kills Park administrator for the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Landscape architect James Corner won the competition to convert the site into a park. With a lot of community input, design and permitting began in 2008. The park hopes the first 20 acres will open in 2015. “You have to have the long view with this park,” she says. “It’s another 15 to 20 years before it fully comes on line.”

Landscape architect James Corner won the competition to convert the site into a park. With a lot of community input, design and permitting began in 2008. The park hopes the first 20 acres will open in 2015. “You have to have the long view with this park,” she says. “It’s another 15 to 20 years before it fully comes on line.”

Still, the park already has held events on the site, providing for opportunities for citizens to bike, kayak, take guided tours, do bird watching. “The Audubon Society says this is a great place to see birds in New York City because there’s an expanse of meadow that is not available generally here,” Hirsh says.

But to even get to this point, Hirsh gives a lot of credit to the work the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) did to prepare the site. “If it weren’t for Sanitation’s stewardship a park just wouldn’t be possible. You have to make sure it’s safe; you have to make sure you have areas that are buildable. You have to make sure the public has access to the things that are beautiful.”

But to even get to this point, Hirsh gives a lot of credit to the work the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) did to prepare the site. “If it weren’t for Sanitation’s stewardship a park just wouldn’t be possible. You have to make sure it’s safe; you have to make sure you have areas that are buildable. You have to make sure the public has access to the things that are beautiful.”

The city had plans for Fresh Kills since the 1940s, ranging from commercial/industrial redevelopment to ball fields, says assistant commissioner Phil Gleason, who heads up the DSNY’s landfill engineering unit.

During the design competition, “We tried to make people sensitive to all the considerations of site, which included environmental controls infrastructure in particular,” Gleason says. There were perimeter cut-off walls, leachate control and an active gas recovery system. Some designers were intimidated by the restrictions, but others saw it as a blank palette for creation.

Because the park would need a road system Gleason’s department worked on a closure construction that could support that. To make the gas collection system accessible but compatible with the public they incorporated

manholes.

The Roots of the Problem

Gleason says to work with regulators the DSNY tried to follow the design guidelines already approved by the state. “But public access does change some things. Still, by analyzing those impacts you can demonstrate it’s still compatible with all the pieces there.”

The DSNY wanted to allay settlement concerns and verify where rigid structures could be placed. This also affected how the DSNY approached post-closure care. To further complicate soil issues, the state of New York has different soil regulations for different applications, so the soil for a park has to meet a certain standard.

The DSNY has researched root systems of trees to know how much soil is needed, ensuring the roots wouldn’t penetrate the barrier layer. And with birds now nesting in summer at the site, the DSNY has learned not to mow grass then to avoid disturbing their habitat.

The DSNY has worked to educate the park on the constraints from the beginning. So far it’s been only perimeter areas and the monitoring system they’ve had to deal with. While the goal is to make the park as natural as possible, the environmental protections are essential. “If we’re inhibited from being able to maintain these operations, they won’t be able to operate the park in those areas.”

Then there are financial issues, of what is a park operation cost and what’s a post-closure care cost.

“I will not say we have everything worked out, because we don’t,” Gleason says. “But we’ve worked it out pretty well so far.”

When it’s complete, Fresh Kills Park will have typical recreational facilities, such as bikeways and horseback riding. Plans call for experimenting with urban farming, using goats or sheep for vegetation management. And the park will work with academic institutions for ecological research.

Hirsh says park operators have faced challenges of high costs, regulatory obstacles and ambivalence to the site by the public, which is concerned about safety. But operators remain excited about the project.

All Together Now

As with an active landfill, getting the public to embrace post-landfill use can be challenging. “That’s why it’s much better when there is a plan in place because you get more buy-in from the local siting groups and planning agencies,” Schubert says. Waste Management often will provide community members with renderings of what the proposed end-use will be, and solicit public input, says Jennifer Andrews, director, corporate communications & community relations for the company.

But if a project can capture citizens’ imaginations, as Fresh Kills Park has, people will be excited about what the final site will be like, even if it’s 10 to 15 years away, Morris says.

But if a project can capture citizens’ imaginations, as Fresh Kills Park has, people will be excited about what the final site will be like, even if it’s 10 to 15 years away, Morris says.

Similarly, it’s key to bring the government into a project as early as possible. “That’s really what drives the acceptance of a landfill project, the end use,” Schubert says.

And the regulatory community needs to work with the host community as well, Morris adds. “It’s important to get the host community to think about that piece of land as an asset that they will have access to and be able to use rather than a liability.”

And the regulatory community needs to work with the host community as well, Morris adds. “It’s important to get the host community to think about that piece of land as an asset that they will have access to and be able to use rather than a liability.”

Morris continues to see regulatory reluctance to accept alternatives to well-established closure methods. And landfill owners can be reluctant to invest in the kind of proactive measures needed for greater flexibility, because that’s something that requires additional upfront capital.

“But it’s something that’s moving from never really being considered at all to something that is at least now being considered,” he says.

Landfill operators can get more buy-in from governments that do “greenbelt” planning if the landfill can be part of a larger development project, Schubert says.

While landfill reuse projects can be funded privately, publicly or a combination, Morris says it’s often the landfill operators that are looking to offset post-closure and financial assurance costs, or private developers that invest in the ventures, rather than public entities.

A beneficial reuse option for the site can help make the landfill closure and next life an economically viable project. “It should get to a level that the care activities that remain can be paid for by the self-sustainable activities that are there,” Morris says.

Or the result, like Freshkills Park, can turn a perceived eyesore into something aesthetically quite different. “When people come and actually get onto the site and see how beautiful it is perceptions change, and that’s certainly one of our goals,” Hirsh says.

Allan Gerlat is News Editor for Waste Age and waste360.com.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)