Can We Love the Aluminum Cup?

In order to do so, we need aluminum to be the best product it can be.

Some folks might think it’s a sad day for our college football team when the talk of the town is about the new stadium beverage cup. Then again, this isn’t just any old cup—it’s a shiny, new aluminum cup, and it was all the rage in Boulder, Colo., this past fall where it debuted at the football stadium as a replacement for traditional single-use plastic cups.

The timing of the cup launch was no accident: Images of sea turtles choking on plastic and beaches covered with more plastic than sand are driving a visceral reaction to plastic. In response, an “anything but plastic” movement has erupted around the globe. As people search for instant alternatives to plastic, the new aluminum cup has found a welcoming audience. And yet, everywhere I go, from national conferences to local coffee shops, the conversation about the cup follows the same pattern: after talking about the benefits of aluminum, the conversation inevitably hits an awkward silence before someone asks the question that we’re all wondering: “But is it really better than plastic?”

Unfortunately, simply swapping out single-use plastics for another single-use alternative, whether it is aluminum, paper or compostable bioplastics, doesn’t just miraculously solve the problem. Before we replace one product with another or decide what is the best choice for the environment, we need to consider the data behind how our products are created, or we risk simply trading one environmental disaster for another. This also includes examining our assumptions of when single-use products are needed or can be replaced with reusables.

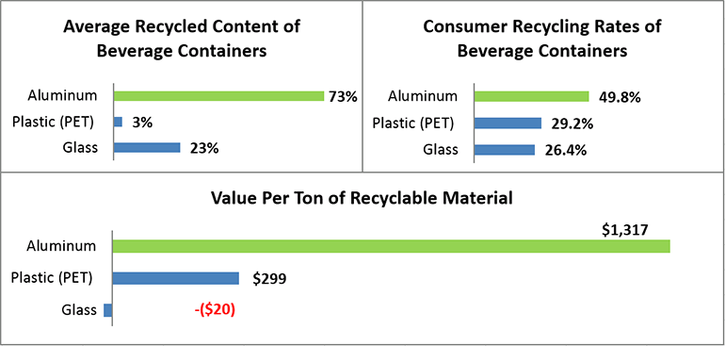

Let’s look first at where aluminum has the edge on plastics (see charts below for more details):

It can be infinitely recyclable.

It has a higher recycling rate.

It is made with more recycled content (on average).

It is one of the most valuable commodities in the recycling stream.

It can reduce contamination in recycling and composting because it’s more easily recognizable as recyclable, as opposed to the confusion about where to sort either traditional plastic cups or compostable, “look alike” polylactic acid (PLA) plastic cups.

Yet, that isn’t the whole picture. Aluminum production causes significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, emits pollutants toxic to human health (both cancer and non-cancer effects), increases acidification potential and freshwater ecotoxicity and is linked to human rights violations. To make an informed decision about whether aluminum or plastic is better, we need to compare both the pros and cons of both materials. To do this, we need to use a tool called lifecycle analysis (LCA), which is a systematic analysis of the environmental impact of products during their entire lifecycle (production, use and disposal).

No LCA studies are available to directly compare the aluminum cup with polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic or PLA compostable plastic cups, so we have to look to LCA studies on aluminum cans versus plastic bottles to get a general comparison. The landmark report on this topic is a 2009 study comparing glass, aluminum and PET plastic to see which is the better container for soft drinks. The study concluded in favor of PET plastic, finding that plastic bottles produced less solid waste, less greenhouse gas emissions and used less energy compared to aluminum and glass containers. This is largely because making new aluminum requires high amounts of energy to smelt the aluminum and make the aluminum sheet, and there is a large amount of waste produced in the mining and production process. (The aluminum industry fought back against the study, claiming its production footprint is shrinking and that its GHG emissions were overstated.)

While plastic currently holds an edge over aluminum, we also need to look at how this might change as our recycling system evolves toward a circular economy. A different LCA study, conducted by CarbonTrust, compared the greenhouse gas impacts of aluminum versus plastic in both the current scenario and future projected scenarios. In the “best case” scenario where both plastic bottles and aluminum cans are assumed to have very high recycling rates and very high recycled content, the result was a tie: both containers were about equal in terms of carbon pollution, with about 35 to 85 grams of CO2 embedded in every 330-milliliter package.

This means that if a single-use container is necessary (and that’s a big "if" for another blog), then aluminum has the potential to be better than plastic after we factor in the devastating impacts of plastic pollution in our oceans and to our wildlife. But having the potential to be better isn’t good enough—if we are really going to embrace an aluminum cup as a better alternative and not just a convenient substitute for plastic, then we need an aluminum cup that actually is infinitely recycled in practice, not just in theory. The U.S. currently recycles only half of our aluminum cans, down from a high of 65 percent in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, leading countries like Germany, Finland, Norway and Belgium recycle more than 96 percent of cans.

Now is a good time to be in the aluminum business as the “anything but plastic” movement surges forward, but we cannot let the industry rest on its laurels just because its products are not ending up in the ocean. We need aluminum to be the best product it can be—which means fully recycled, made with the highest levels of recycled content, produced in facilities using renewable energy and made using safer alternatives to the current BPA plastic coating inside cans. I look forward to the day I can raise a cup and cheers to that!

Kate Bailey is the policy and research director for Eco-Cycle and helps citizens, government staff and elected officials implement zero waste solutions.

About the Author

You May Also Like