University of Michigan Study Informs on Plastic Waste, Barriers and Opportunities

We hear routinely that plastic packaging is a major source of waste and will continue to be at the rate at which it’s generated; these mass-produced, short-lived commodities were the largest market for U.S. plastics in 2017—but actually two-thirds of plastic used that year entered markets other than packaging. Meanwhile, a huge influx of other plastics, with applications from auto parts to building materials and electronics, present unique end-of-life challenges, as well as opportunities, to promote a circular economy. The “plastics packaging surprise,” and a call to look at other plastic applications, are main takeaways from a new University of Michigan study published in the journal, Environmental Research Letters.

The research project was supported by a grant from investment bank and financial services firm Morgan Stanley, who has a goal to prevent, reduce, and remove 50 million metric tons of plastic waste by 2030. The university researchers they turned to for information to help them reach for their target began with a specific goal and strategy in mind.

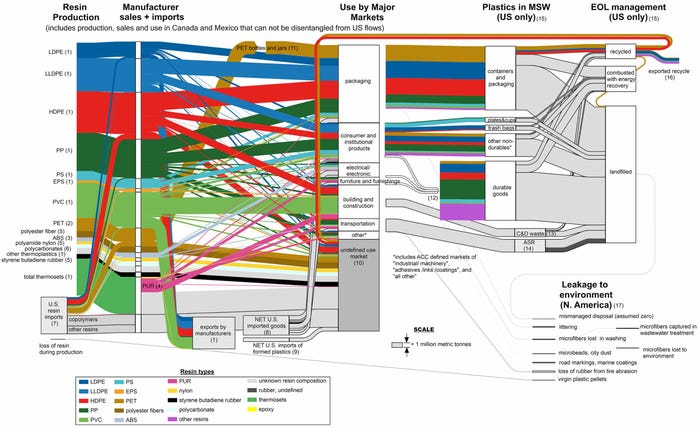

“To reduce plastic waste, we need to first understand the types of plastic resins going into the economy. We need to know how it’s used in what markets, and we need to know what the current practices and outcomes are for managing it at the end of life. So, we developed a characterization of plastic material flow in the U.S. to better understand and improve its use in the future,” says Gregory Keoleian, senior author of the paper and director of the Center for Sustainable Systems at the University of Michigan.

As part of their research project, Keoleian and his colleagues created a map of the flow of plastics, from production through use and end of life, tracking these materials by plastic type and markets. The map is intended to help guide industry, policy makers, and researchers to be able to accelerate plastic waste reduction.

© The Author(s). Published by IOP Publishing Ltd. CC BY 4.0

The University of Michigan study was conducted, and the map created in response to a pressing realization: “We need to reuse plastic waste and move toward a more circular economy, but there are some barriers to do this. On the front end, plastic feedstocks are inexpensive, and on the back end, there are low tip fees in many regions. So, we have a linear economy where we extract, use, and dispose,” says Keoleian.

Steve Alexander, president and CEO of the Association of Plastic Recyclers, read the report with interest and shared a few thoughts on its focal points.

“Packaging is a small part of the stream but remains the focus of the public because that is what they see on a daily basis. The system needs to address the entire composition of plastic material, disposal, and reclamation.

Many plastics, as stated in the report, do not biodegrade. Therefore, the durable goods that the report discusses are a landfill issue, like all other materials. Some of the durable goods have recycling options, but those options are different than the systems designed to recycle packaging, [and require consideration],” he says.

The researchers went a step further than simply showing the flow of existing resins throughout their lifecycle; they also characterized potential specific scenarios for end-of-life management of some resins.

“For instance, if you convert all plastic from the municipal solid waste MSW) stream to energy –and there are 32 million metric tons of plastic it could make 4 percent of the electricity needed in the U.S.,” says Keoleian.

Another scenario illustrated in the study involves making fuel via pyrolysis from the 28 million tons of plastics landfilled each year. The outcome in this case would translate to generation of about 7 billion gallons of liquid fuel, which is equivalent to about 15% of diesel consumed annually.

So, the map informs on current processes for managing specific waste streams as well as outcomes – which in this case is that 8% of plastics are recycled and three-quarters are landfilled. And it allows the industry to develop “what if” scenarios, to inform on potential to recover resources.

“It’s a way to visualize current practices that are resulting in lost resources, as well as understand opportunities to achieve a more circular economy,” says Keoleian.

The researchers also aimed to provide context for understanding challenges. Among those challenges are finding substitutions for these plastics. And in many cases, they are hard to separate. Adding to these barriers is that there is a huge stock in use today as manufacturers are making products that have longer lives than single-use packaging. So, it’s accumulating over time; 400 million tons of plastic are now in use in the U.S., which is eight times the amount that was manufactured this year alone.

[So], we need solutions to better manage all of these materials when they get retired,” says Keoleian.

Nina Butler, CEO More Recycling, Chapel Hill, N.C., punctuates the point that we have insufficient infrastructure: “More than two-thirds of what's produced each year is not intended to be handled by our current recycling system, which is why I’m thankful to see this study from the University of Michigan. We live like superhumans thanks to plastics—flying, communicating with people beyond earth's atmosphere, replacing joints and organs … But we must reconcile the fact that our use of plastics enables the continued growth of the human species, but that living beyond natural boundaries comes with a serious cost.”

Butler says managing plastic in the environment will require coming to terms with technical barriers, with a large one being lack of transparency.

“If we had a transparent marketplace that shows the life cycle impact of our consumption we would unlock innovation needed for reverse logistics, chemical or molecular recycling, and other steps in recovery (color sorting, food-grade-level processing) that are necessary for a truly circular economy,” says Butler.

About the Author

You May Also Like