Rethinking the Way We Manage, Repurpose Waste

Key highlights from the 2018 EEC/WTERT Bi-Annual Conference at City College of New York.

Waste-to-energy (WTE) solutions, the concept of a circular economy, end-of-life product design and potential opportunities to help combat contamination and improve safety across the industry are just some of the topics discussed during the 2018 EEC/WTERT Bi-Annual Conference.

The conference took place October 4 and 5 at the Earth Engineering Center (EEC) at the Grove School of Engineering, City College of New York. Here are some of the key highlights from the event.

Circular Versus Linear Economies

Henrietta Goddard, a research analyst at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, kicked off her discussion with the main principles of a circular economy:

By thinking about the impacts of the materials from the very beginning of the design process, waste and pollution can be significantly reduced.

Products are designed to stay in use and keep circulating to regenerate natural systems.

When deciphering the differences between a linear economy and circular economy, Goddard explained that although the current linear economy has brought increased wealth, it has also helped generate more waste. But in a circular economy, a laptop, for example, would be kept as long as possible; it would be durably built and designed to last.

She also pointed out that food waste is another big problem. And one of the most frequently wasted food items is bread. Again, in a circular economy, discarded bread could be recycled and reused, say in the brewing business to make beer. Furthermore, organic materials that can’t be used again could be anaerobically digested to create fuel, she added.

“Circular economy makes sure that designing doesn’t hurt the environment,” said Goddard. “It is important to think about linear versus circular systems and how [a circular system] could be incorporated into your businesses and day-to-day operations. Collaboration is key when it comes to creating systemic change.”

Kathryn Garcia, commissioner for the City of New York Department of Sanitation (DSNY), which collects about 10,000 tons of trash and 2,000 tons of recyclables a day, said that the city, “unfortunately,” is still a linear economy. But Garcia and Mayor Bill DeBlasio’s administration are looking to change that.

New York City is three years into its ambitious goal of sending zero waste to landfill by 2030.

“What I like to say is ‘I am not the one creating the waste. You are the one creating the waste,’” Garcia said to conference attendees. “I am the one creating the programs, so you can achieve zero waste.”

She also stressed the importance of a dual partnership between the department and New Yorkers. The city is currently working toward community engagement to divert the organic portion of waste from landfill because that is where greenhouse gases come from. Garcia explained that compost facilities in and around the city have given materials back to parks and city landscapers, so New Yorkers actually get back the materials they want to see used.

“This is really about New Yorkers being able to see a product that they can get from their waste,” she said. “But we have built on this for a long period of time. There has been dedication from a lot of community composters over the last 25 years doing backyard composting, teaching master composting classes and running waste drop-off sites. They have been the pioneers who said, ‘New Yorkers will bring you your waste if they can make it into something that is useful.’”

And though it might not seem like much, textiles comprise 6 percent of the waste that ends up in the trash every day in New York City. The problem, according to Garcia, is that people do not keep their clothing anymore, despite the fact that there is a robust nonprofit sector that will reuse clothing—Goodwill and Salvation Army, for example.

Not unlike many municipalities around the country, household hazardous materials, shopping bags and electronics have been challenging items for the city to manage. So, the city is working hard to try to eliminate nonrecyclables from the waste stream. The City Council passed legislation to put a fee on plastic bags, and DSNY has distributed 300,000 reusable 0x30 bags on the subways and in area communities.

DSNY has also spent much of its efforts trying to ensure the city diverts old electronics for recycling or proper disposal. In 2010, a law was passed saying these materials could not end up in the waste stream, and due to household drop-off programs and legislation, DSNY saw a 60 percent decrease in e-waste disposal after implementing an e-waste disposal ban.

Finally, the department is working with and actively trying to engage the housing authority to promote recycling. One of the biggest challenges has been building infrastructure, which wasn’t designed for waste. Garcia pointed out that community engagement remains a challenge since these communities don’t have lobbies or places for residents to gather.

“Trying to figure out how to, one, engage with residents but also give them the ability to do it right has been a struggle. But it is something we are continuing to work on,” explained Garcia.

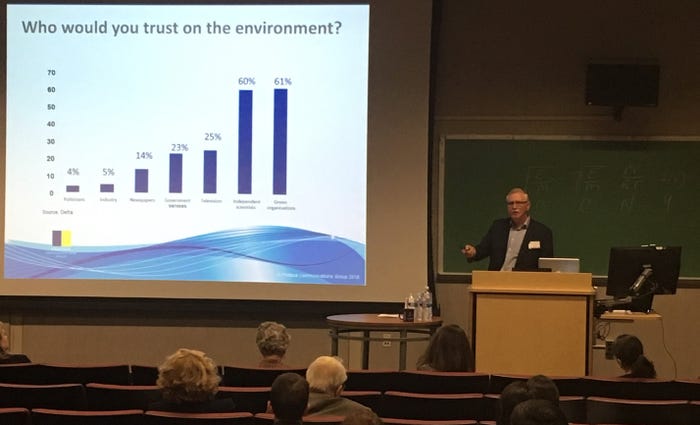

Public Engagement and Perception

Paul Davison is the managing director of Proteus Communications Group in the U.K., and he loves talking about waste.

“Waste is my favorite subject, and the reason why I love waste is because most other people hate it,” he quipped, noting public attitude is absolutely critical to delivering to the circular economy.

“Can I just say for a minute, never use the phrase ‘circular economy’ with the public. They’ll have no idea what you’re talking about, and if you use jargon like that, they will stop listening to you straight away, because that’s an exclusive language,” he said. “They will think you are trying to be better than they are and that you are trying to con them. We have to watch the language we use when we’re talking to the public.”

According to Davison, there are some simple processes that can be used to educate the public. He stressed that when talking to the public about energy-from-waste (EfW), generally speaking, the public will think of a facility that emits noxious fumes and will likely have a dated view of the way technology works. Ultimately, people will think filth and dirt.

But realistically, he pointed out, the industry has to better drive home the benefits of advanced technology and getting value out of something that is actually waste.

“In Denmark, when I am talking to people about energy-from-waste, I don’t have to explain to them the advantages. They know it. And we need to share that with other communities that don’t know it,” explained Davison. “I generally believe that the United States has a great opportunity to replace some of the filthiest, decrepit and out-of-date energy-from-waste plants I’ve seen on the planet. You’ve got to clean up those energy-from-waste plants. This technology is clean and has a purpose, and its role in a circular economy is essential. If you just show the public the dirty technology that is here in America, you will reinforce that image to the public, and it will make your job engaging the public that much harder.”

Davison pointed to three disconnects between the public and waste:

Disconnect 1: People don’t view it as their problem, that it is their waste. “We need to get the public to be prepared for change and to understand that it is their problem,” he stressed.

Disconnect 2: Over the last 10 to 15 years, the focus on recycling has isolated residual waste disposal.

Disconnect 3: Waste and resources are not the same thing. “We have to talk about it the way the public thinks,” he explained. “The last thing you do is leave it to the engineers to come up with the terms of communications. The engineers will save the planet, but when it comes to communications, I wouldn’t leave it with them. If you leave it with them, you have stuff like brilliant anaerobic digestion. But when we went out to the public and asked what they think anaerobic digestion is, we got answers ranging from something you have to go to the hospital for or something that will ruin your holiday. So, don’t leave it to the engineers to come up with a communications solution.”

In addition, Davison discussed challenges of EfW adoption, including:

In some countries, energy-from-waste is seen as an unacceptable technology. In some U.S. states, it’s still banned.

The internet allows outdated and inaccurate information to continue to be circulated via social media.

The waste sector does not invest enough in proactive reputation management.

Opportunities for Change

Mallory Szczepanski, editorial director for Waste360, who also spoke during the conference, discussed the recent efforts to reduce plastic waste and marine litter, new technologies—optical sorters and robotics—and emerging opportunities that materials recovery facilities (MRFs) could implement to help combat contamination and improve safety amid China’s waste import ban.

“A lot of people view the moves from China as a crisis, but some people view it as an opportunity,” said Szczepanski. “There are opportunities for more domestic infrastructure, more recycling, new best practices to be implemented and new partnerships to be formed.”

She went on to explain that the waste and recycling industry can work with other industries like the design and manufacturing industry to ensure that products and packaging are designed with end of life in mind.

“Product designers and manufacturers should be thinking about waste in the beginning of the design process, and there are a lot of steps people and businesses are taking to do just that. Furniture companies like Steelcase and Herman Miller are just two examples of companies that are designing products for end of life.”

She also spoke about the issue of contamination, which is an ongoing challenge for the industry. By ramping up education efforts, improving recycling programs and utilizing new technologies, contamination can be reduced and materials entering the recycling stream can become cleaner, she stated.

Touching on the growing problem of marine litter and plastic waste, Szczepanski discussed the Great Pacific Garbage Patch cleanup efforts, the state of California’s recently passed plastic pollution reduction bills and the Save Our Seas Act of 2018 and the growing number of establishments and municipalities banning plastic bags and single-use straws.

In closing, she spoke about the future of the industry and some of the changes the industry may see in the near future, including more technologies coming online, possibly more waste reduction bills brought to the table and more changes within companies and recycling programs as China’s list of banned imports expands later this year and next year.

Craig Cookson, senior director, recycling and energy recovery, for the American Chemistry Council, noted that according to the most recent data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 68.6 percent of plastics packaging goes to landfill.

“We need better data to achieve the goal of packaging that is reused, recycled or recovered by 2040,” he said.

In order to achieve that goal, Cookson stressed that educating consumers is critical, as well as developing a breakthrough and disruptive technology that will really change the way things are done now. He added that the key to a circular economy is including the energy and chemical companies in the chain.

“Next to natural gas and crude oil, the nonrecycled plastics that we’re throwing away are the third biggest provider of fuel,” he pointed out. “So why are they going to landfill, but we’re still digging up oil? Let’s think about innovation to dig our way out of these problems and not focus on bans.”

When thinking about MRFs of the future, the American Chemical Council formed a group, Materials Recovery for the Future (MRFF), several years ago to study new technology that can sort materials, as well as study ways to reduce contamination at MRFs.

The State of WTE in China and the U.S.

During the second day of the conference, Prof. Qunxing Huang of Zhejiang University in China spoke about the progress of WTE in China. He shared that from 2006 to 2012, municipal solid waste (MSW) in China increased at an average rate of 4.5 percent, and that from 2014 to 2017, MSW in China increased at an average rate of 7 percent.

"[Looking forward,] we predict that in 2025, we will manage 429 tons of MSW per year for all of China, and in 2035, we will manage 547 million tons of MSW per year for all of China," he stated.

As of 2017, China has 296 WTE plants in operation, burning 102 million tons of MSW every year. The country has another 120 plants under construction and 102 more in planning.

In the U.S., WTE makes up only about 13 percent of the industry.

Bruce Howie, P.E., vice president and professional associate at HDR Inc., kicked off his presentation with a timeline of the WTE industry. In the 1950s and 1960s, construction of early WTE facilities began in Europe and construction of incinerators started in the U.S. In 1975, construction began on the first WTE facility in North America, which was located in Saugus, Mass. The 1980s, according to Howie, were the "hay days" of WTE in North America. And the 1990s were the "dark ages," because there were stricter emissions standards in the U.S. that led to retrofits and some facility closures. The 2000s brought expansions to existing facilities and construction of new facilities in Europe and Asia. Today, there is some development of new facilities, but tough economics are leading to some closures.

He went on to say that there are many challenges to change in the U.S., including there's no regulatory or policy framework currently in place to incentivize programs, there's limited to no funding or support to look beyond the traditional linear business model and there's no compromise between parties and stakeholders on either side of the aisle.

That being said, he shared that the key drivers of the expansion of WTE include a push for greater diversion from landfill, an enhancement of the "3Rs" programs and organics collection programs, the idea of waste is a resource (the fourth R) and an interest in alternatives to traditional waste-to-energy technologies like mixed waste processing and anaerobic digestion.

While those key drivers are "doable," there are some key inhibitors to the expansion of WTE, including the fact that it's cheap to landfill, energy prices and fuel prices are relatively cheap (at least in the U.S.), there are many groups who oppose the idea of WTE and there are a number of regulatory factors to consider, such as carbon taxes and greenhouse gas legislation.

About the Authors

You May Also Like