Ins and Outs of Multifamily Unit Recycling

Because it’s easy to be anonymous in high-rise buildings, it’s hard to tell who’s not following the rules when it comes to recycling.

As municipalities double down to boost their recycling numbers, they meet challenges unique to multifamily building communities. Prevalent cultural diversity calls for communicating expectations in different languages. A transient population means education must be ongoing. And because it’s easy to be anonymous, especially in high-rise buildings, it’s hard to tell who’s not following the rules.

But overall, most residents want recycling—at least that’s what AMLI Residential, a national multifamily property developer, learned.

“Sustainability is a bigger demand than ever, and we found that 83 percent of our residents recycle,” says Erin Hatcher, vice president of sustainability for AMLI Residential.

It takes thought and planning to make it work. That’s why the Manhattan Solid Waste Advisory Board (MSWAB) came to be in 1989. MSWAB works with the City of New York Department of Sanitation (DSNY), other city officials and recycling businesses to improve recovery practices and results.

But even 30 years after recycling became mandatory in New York City, the recycling rate is 20 percent, “and it��’s hard to get further in a densely populated area with so many apartments, especially a lot of high-rises,” says Jacquelyn Ottman, chairman of MSWAB.

MSWAB has learned some ins and outs. For one, if their neighbors are recycling, people will usually follow suit, even if they don’t own their properties (renters are sometimes less motivated).

“No one wants to have the pink sticker on their door when they get caught doing something wrong. But there is enforcement, and then there is dangling the carrot of peer pressure. If you know your neighbors and they recycle, you are more likely to do it,” says Ottman, who holds meetings with residents and points out the embracers.

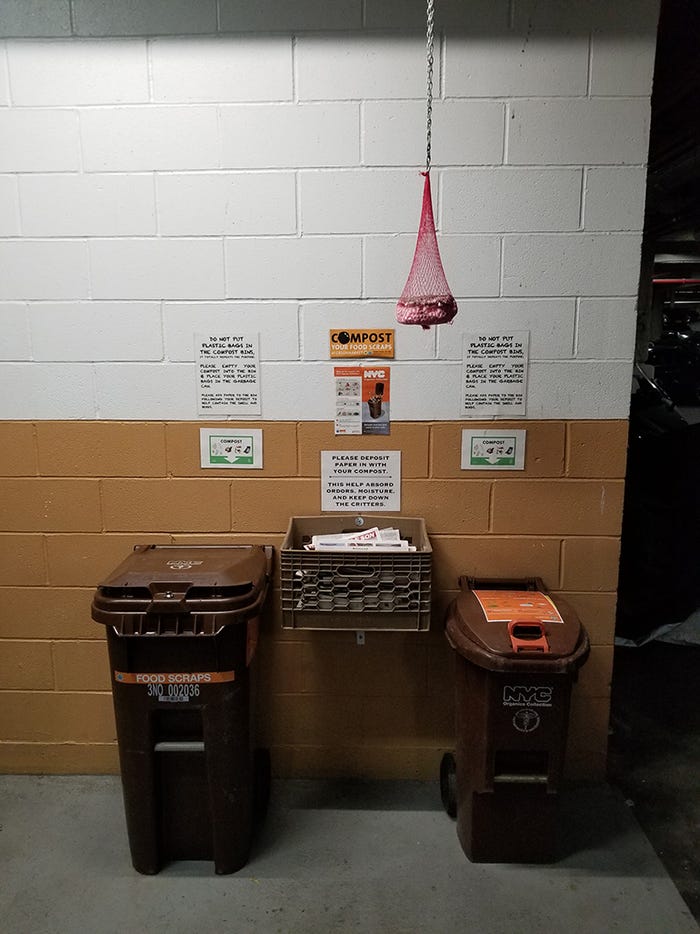

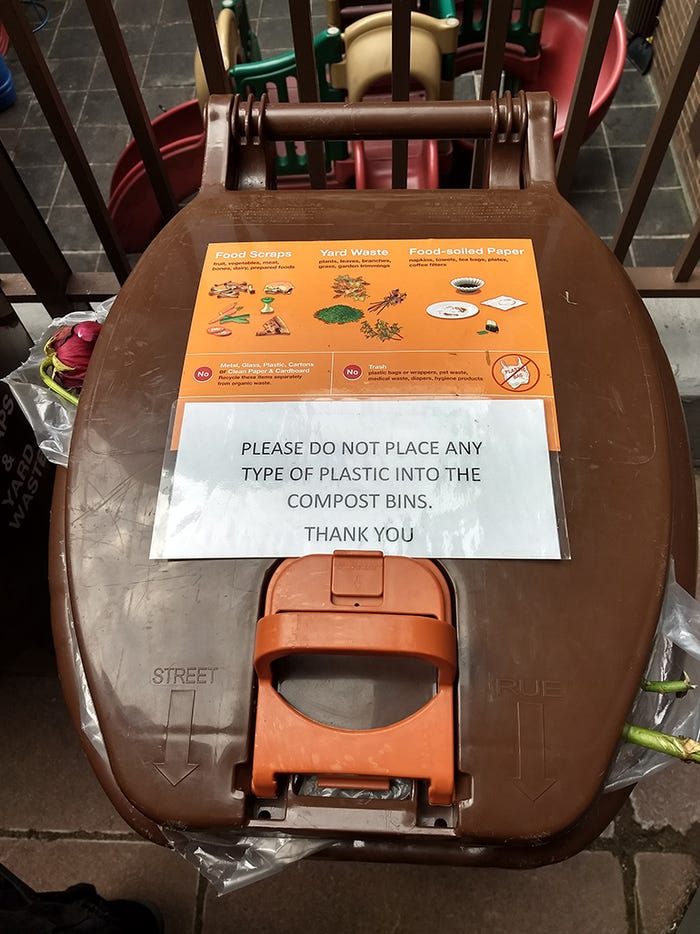

Organics can be tricky; residents typically need to haul them to a basement. But they’re inclined to participate if they are given countertop caddies. This investment underscores that building management is serious, and it makes residents’ jobs easier, notes Ottman.

DSNY sends trucks on different days for different materials, requiring building staff to know schedules, locations and what goes in each container, and residents must understand what to sort. So, there is emphasis on educating everyone involved.

MSWAB has put out guides, primarily for building owners and property managers, that include tips and best recycling practices from around the city.

No two properties have the same site plan; additionally, recycling areas are not commonly part of the initial building design. These are reasons AMLI is working with an architecture firm to ensure the most appropriate setup at each site for a successful recycling program. It may, for instance, be dual chutes, one for trash and one for recycling; a single trash chute with multiple recycling centers; and/or valet service at residents’ doors.

Strivers Gardens in New York City has chute rooms on each floor, where there’s one bin for paper and cardboard and one for plastic bottles, cans and glass. Staff sort material, transfer it to larger wheeled bins, roll it to the basement, then move it to the curb.

Signage has been a big part of keeping it simple, especially for residents. Strivers posts color-coordinated signs with pictures and added signs with just a few words in high-contamination areas.

“For some, pictures are clearer. But not everyone will understand color coordination on those signs, and they may also be more verbal. We added the signs with words hoping to reach people we may have missed, and it worked. Our contamination rates went down,” says Martin Robertson, facilities manager of Strivers Garden.

Strivers residents also recycle organics, taking them to the basement in small containers. They can leave electronics on the lower level, and porters transfer them to a designated bin in the basement. There are also bins in the laundry rooms for textiles that are picked up for donation.

In 2020, a multifamily recycling ordinance goes into effect in Dallas, where about 55 percent of residents live in apartments.

Properties with eight or more units will be required to offer recycling for a minimum of 11 gallons of material per unit per week. This includes paper, carboard and containers made of plastic, glass and metal.

Management will have to report captured materials, and the city is providing them with recycling capacity calculators to do so.

“So, when we talk about 11 gallons, they know exactly what that means. They can enter number of units, number and types of containers and collection frequency to learn if they made the requirement,” says Danielle McClelland, environmental quality and sustainability division manager for Dallas.

Beacon Communities has 52 multifamily properties in Massachusetts. Currently, recycling and trash are co-located, but Neil Young, assistant vice president of landscaping, is about to try an experiment: relocating recycling to try and reverse a problem where people are putting recyclables in the trash and vice versa.

“I want to see if new signage on the dumpster, a banner on the fence enclosure and plastic balloons that say Beacon Recycling Center will make it clear that this is a recycling area. It’s not for trash,” he says.

Young believes results are also impacted by whether umbrella property management companies engage with onsite managers.

“I ask onsite staff how it’s going, listen to problems and make changes based on their opinions,” he says. “This is important because they will see upper management buys into it and will support them. Working as a team and listening matters.”

About the Author

You May Also Like