2015 Coal Ash Rule Continues to Spark Controversy and Change

The Obama administration’s coal combustion residuals (CCR) rule established standards to provide comprehensive requirements for the safe disposal of CCR.

The management of coal combustion residuals (CCR) is a controversial topic, especially since the introduction of a game-changing federal rule four years ago that has sparked ongoing debates, implementation delays and policy tweaks.

The Obama administration’s 2015 CCR rule established standards to provide comprehensive requirements for the safe disposal of CCR. Namely, the regulations address risks associated with groundwater contamination, set reporting requirements for landfills and impoundments that receive coal ash, establish rules around closure and post-closure care and restrict where these sites can be located.

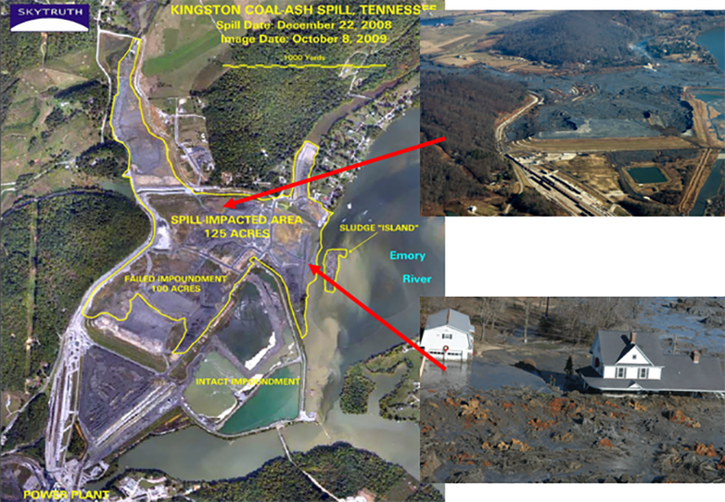

This rule follows a few highly publicized events, including spills at the TVA Kingston plant in Tennessee and at the Duke Energy site in Eden, N.C.

Estimated costs to comply with the CCR rule range from $7.3 billion to $34.7 billion, depending on the source of these figures. And an additional $39 billion could be added to the overall cleanup cost as the result of a recent D.C. Court of Appeals ruling.

The Trump administration has pushed through several amendments to the policy that would afford more leniency and cost savings to the industry. As amended, states or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has authority to suspend groundwater monitoring requirements when there’s no evidence of potential for migration of hazardous constituents to certain locations. And noncompliant sites were granted more time before they must stop receiving waste and close.

Environmental groups have put up a fight. They insist these sites need more stringent overarching mandates. Meanwhile, as conversations continue over the evolving regulatory landscape, the industry has experienced disruptions and uncertainty.

EPA’s 2015 CCR rule was, for many states, the first time they had any regulations on CCR management, says Rick Buffalini, vice president of Civil & Environmental Consultants.

“I work in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia, and while they had established comprehensive regulations, we’ve had to take additional measures. For instance, there are more rules requiring these states to demonstrate compliance with structural stability. And they now have more location restrictions,” he says.

A more recent significant change is around a looming deadline. In the original rule, any unit that did not meet the aquifer location restriction standards had to initiate closure in six months. Unlined units in violation of groundwater protection standards also had to initiate closure in that timeframe.

“Last year, the EPA extended the closure deadline for units not meeting these two standards until October 2020, as we were clear that the earlier timeframe was not sufficient to build replacement facilities. That provided 18 more months to build disposal capacity and wastewater treatment capacity,” says Jim Roewer, executive director of the Utility Solid Waste Activities Group.

There have also been changes around liner requirements. The original 2015 rule required existing sites to have 2 feet of clay, and sites that opened after 2015 had to have a composite liner of clay and another layer. In 2016, only 20 percent of existing coal ash impoundments reported to have liners meeting these specifications.

Then, in August 2018, a Washington, D.C., Circuit Court of Appeals ruling tightened the requirements further, leading to more disruption. All operators must now have a composite liner of a geomembrane and compacted soil, which will force at least 100 more facilities to shut down, according to Roewer.

While these rules are clear, at least for operational sites, he says there are some ambiguities around requirements of inactive facilities. Standards for these facilities are not clearly defined, he says. Further, he argues, federal policy does not provide regulatory certainty and clarity through a permit process.

“Right now, utilities may have to comply with two rules: a self-implementing federal rule [enforced only through citizen suits] and the state’s requirements. We want one permit that incorporates the federal rule. And we want it to be issued and enforced by the states,” says Roewer.

While authorizing states to create a permit program does create somewhat of a patchwork, there always have been both state and federal environmental rules. Plus, the minimum requirements under federal law will always apply in every state, creating some uniformity, contends Abel Russ, senior attorney for the Environmental Integrity Project.

Still, the federal CCR rule reaches only so far. One of Russ’ concerns is that with old dumps, many states are not taking action when there are potential contamination issues because the federal rules doesn’t apply to those sites. Although some states have been proactive.

“Georgia is applying the federal coal ash rule framework even to sites closed before 2015. We hope more states will follow their lead,” says Russ.

Georgia requires utilities to obtain a solid waste handling permit to store coal ash at shuttered plants, as well as at sites that have not closed but are inactive. Inactive and shuttered plants must disclose groundwater monitoring data and soon will be required to supply additional information, such as their location relative to aquifers and to wetlands and fault areas.

More revisions may be in the pipeline. EPA recently released a prepublication version of additional provisions, for instance allowing more coal ash to be exempt from the rule as beneficial use.

As coal ash rules are finetuned and enforced, who will come out ahead?

Based on the federal rule’s current provisions, “Those who dispose coal ash and those who build solid waste landfills will benefit. In the instance that impoundments treat it onsite and put it into another impoundment, companies that do the dewatering, supply liners and remediation will be major beneficiaries,” says Ken Leung, managing director at Cronus Partners, an investment banking firm.

“And there will be opportunity for those who convert coal to beneficial reuse,” he says.

About the Author

You May Also Like