The Impacts of PFAS and a Push for Nationwide Standards (Part One)

Part one of a two-part series looks at the health and environmental implications of PFAS, as well as the lack of research and federal regulation around these chemicals.

Over the last seven years, concerns of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—particularly two specific PFAS compounds—found in drinking water have started to gain momentum due to their potential health and environmental implications. Now, people affected by these chemicals, individual states and U.S. representatives are pushing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to develop a nationwide standard and more stringent regulations to limit harmful PFAS chemicals in drinking water.

On July 24, Rep. Harley Rouda, chairman of the U.S. House Subcommittee on Environment, held a hearing, “The Devil They Knew—PFAS Contamination and the Need for Corporate Accountability,” to examine the history of the science behind the health risks associated with PFAS chemicals; what corporations knew about this science and when they knew it; the current levels of PFAS chemical contamination in the United States; and industry efforts to clean up contaminated sites.

PFAS compounds—manmade, highly fluorinated chemicals found in hundreds of consumer products—have oil-, stain- and water-repellant properties, making them highly desirable for various products, such as nonstick pans, waterproof boots and raincoats and carpets. They are also flame-retardant, which makes them especially useful in firefighting foam.

PFAS chemicals are currently unregulated by the federal government, and this absence of federal action has pushed states to take efforts to regulate PFAS chemicals into their own hands. PFAS chemicals may lead to serious, adverse health outcomes in humans, including decreased fertility, an increased risk of thyroid disease and increased cholesterol levels, and they have also been linked to cancer. PFAS chemicals commonly used in the U.S. have been linked to birth defects and delayed development.

Major corporations that have produced or used PFAS chemicals to make everyday consumer goods, such as DuPont’s Teflon and 3M’s Scotchgard, allegedly knew of the health risks of the chemicals but actively suppressed the information, activists claim. Up to 110 million Americans have been exposed to PFAS chemicals through their drinking water, and PFAS chemicals have also been detected in the country’s food supply.

Because the carbon-fluorine bond of PFAS is so strong and stable, these compounds are persistent, do not readily break down and are often referred to as “forever chemicals.” PFAS, which are highly mobile in the environment in both liquid and air, have been detected nearly everywhere around the globe, including the North Pole. The primary exposure of PFAS to humans is from breathing, eating and drinking. The vast majority of the regulatory initiatives thus far are on drinking water contamination and cleanup.

But two specific compounds of PFAS—perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)—have become the subject of heightened scrutiny based on the findings of a C8 Science Panel study that concluded 10 years ago.

The C8 Science Panel was formed as part of a class-action settlement with 3M and DuPont chemical companies for various participants in the Ohio Valley region who suggested their exposure to the PFOA and PFOS compounds specifically caused them harm. The study found a moderate to suggestive linkage to kidney and testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, all the way to potential cholesterol and prenatal impacts, explained Bryan Staley, president and CEO of the Environmental Research & Education Foundation (EREF), during a July 22 Stifel conference call titled “PFAS—The Latest State of the Science and Regulation Fireside Chat and Q&A.”

The biggest problem with regulating PFAS compounds is there are so many unknowns, and regulations have begun to outpace scientific research. PFAS is the broad term for all of the substances and compounds that exist and include PFOA, PFOS and now another compound called GenX.

“We are starting to see on the consumer front different products that say PFOS or PFOA free, which may be true, but what the consumer isn’t being told in many of these cases is the material itself is likely not PFAS free,” noted Staley. “They’ve just switched to a different sister compound, such as the GenX material. For example, for something that has GenX, the product manufacturer can say, ‘We are PFOA and PFOS free,’ but they are using GenX, which is a new sister compound and there is very little science out there. There are certain toxicology reports out there that suggest similar agents and attributes to these new compounds that would make them similar to PFOS and PFOA. But that’s a very blanket statement and there are nuances to that.”

During this week’s Stifel call, Anne Germain, vice president of technical and regulatory affairs for the National Waste & Recycling Association (NWRA), explained that though PFOA, PFOS and GenX are just three different types of PFAS, she has seen numbers indicating there could be 4,500 or more different types that range in the number of carbon atoms of anywhere from four to 16.

“We don’t know how to test for all of them,” emphasized Germain. “I think the latest test methodology is only approved for 18 different compounds, which was approved last year by the EPA. That kind of gives you a sense of how little we know.”

Germain also pointed out that with respect to PFOA and PFOS, even though those two compounds were voluntarily phased out in the U.S., there is no federal regulation that requires that they not be manufactured, and there is nothing restricting them from being imported. However, earlier this year, under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, there was an agreement to fully phase out PFOA and PFOS.

“That said, there are still a number of exemptions being offered, and the E.U. [European Union], China and Russia all applied for many of those exemptions,” she said. “So, it’s still being manufactured, albeit in much lesser quantities.”

When considering how to manage PFAS, a lot depends on where they’re going. Right now, most of the sampling and research revolves around drinking water.

“We know the PFAS compounds end up in landfill gas emissions, we know they are in compost, we know they are likely in recycled materials that are being repurposed and we know they are in landfill leachate,” Staley pointed out. “Those are very different mediums than drinking water. I know in academic circles there are methods currently under development and certain research labs in colleges and universities that have been successful in developing methods to explore these other mediums beyond drinking water. But EPA has not formally approved to recognize these methods, so study of those methods currently resides in the halls of academia and are subject to approval from agencies like the EPA.”

Staley also pointed to a recent study that came out just this year demonstrating the toxic effects for seven different PFAS compounds beyond PFOA and PFOS.

“Now, when I say toxic effects, I want to make sure the language is clear. That is toxicology, not epidemiology. Toxicology suggests there is buildup of these compounds in the human body or in animals; it doesn’t suggest there is a confirmed linkage of some of the effects I mentioned, such as cancer and thyroid disease,” explained Staley. “This gives us an example of just how untouched research is on the health side. One of the key things about the health implications that I want to emphasize is that the research does indicate that the behavior of all these other PFAS compounds can be very different than the findings of PFOA and PFOS research of [the C8 Scientific] panel. We need to be very cautious about extrapolating findings from all PFOA and PFOS to all PFAS compounds because we simply just don’t know at this point.”

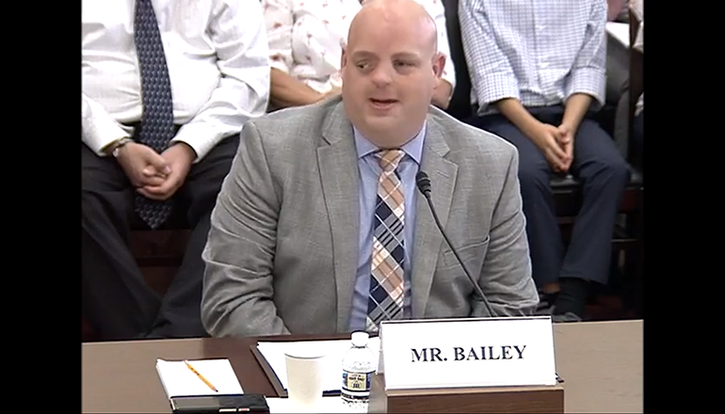

During the July 24 Subcommittee on Environment hearing, U.S. representatives on the committee heard from three witnesses who have lived through and have been dealing with the impacts of PFAS contamination. One of those witnesses was Bucky Bailey, an affected resident and activist who was featured in the recently released documentary on Netflix titled “The Devil We Know.”

Bailey was born in Parkersburg, W.Va., in 1981, with numerous birth defects. He has only one nostril and a serrated eyelid on his right side. He struggled to breathe normally immediately after birth and doctors told his family that it was unlikely he would make it past his first night.

While pregnant, his mother was a full-time employee at DuPont’s facility in West Virginia. Her role at DuPont was to control production of Teflon, and she worked in a confined area with PFAS chemicals C8 and PFOA. Her job was to keep the chemicals under control and push the excess chemicals “out back,” according to Bailey.

After Bailey’s birth and while recovering in the hospital, his mother recalled receiving phone calls from DuPont representatives inquiring about his health. Upon returning to work, she found studies from 3M, a former manufacturer of Teflon, associated with the same birth defects as her son after being exposed to the chemicals. She was reaffirmed by DuPont that C8 was not the cause of her son’s birth defects.

“After dozens of reconstructive surgeries between the ages of 2 and 5, my family moved to Virginia,” said Bailey. “With no health insurance at that time, my parents went to court to demand that DuPont pay for the reconstructive surgeries. However, door after door was closed to us by lawyers who refused to take cases against a corporate giant like DuPont.”

“Today, I have another reason for trepidation,” he added. “With my high levels of the C8 chemical in my blood, will I have to endure kidney cancer? Will I have to endure testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, high cholesterol? Will I have to endure one of those six diseases that were linked to the study? Will I lose my life to one of these diseases?”

“I feel that we, more so than any, have the means to provide everyone with clean water,” continued Bailey. “PFAS discharges should be subject to the federal Clean Water Act. Polluters such as DuPont and 3M should not be allowed to simply discharge PFAS into our water supplies.”

Moving forward, Bailey said he supports adding an amendment that mandates polluters to report their PFAS chemical discharges. He also noted that the federal government needs to take further steps of monitoring drinking water and PFAS contamination levels.

Read part two, which breaks down how some states have taken this matter into their own hands, as well as steps being taken to manage this chemical waste flow.

About the Author

You May Also Like