Guns, Germs & Peels

In 1997, UCLA environmental history professor, Jared Diamond, published his magisterial tome, Guns, Germs and Steel. His book plumed to the roots of how it was that some tribes at the end of the last ice age, but not others, went on to develop technologically advanced civilizations.

The answer, he concluded, laid in the varied geography among the earliest human settlements that gave a leg up only to those who inhabited certain places, but not to others. In the end, he concluded, guns, germs and steel were the agents that enabled the advanced societies to conquer undeveloped peoples, and in 1532, made it possible for 168 Spanish conquistadors to defeat the Inca army of 80,000 men.

For those of us in the waste industry, whether we dump, burn or recycle, we all want to know where our forebears came from and how that animated us and the places that we inhabit today. Even more important, what, we ponder, does the future hold for our descendants? Diamond’s book provides a wonderful taking off point for that journey, once we modify our peels for his steel, so that we may discern the seismic forces that dominate long-term trends and are causal agent for one part of our industry to ultimately, like the Conquistadors, subdue the far larger side.

Germs. For the later inhabitants of the 19th century, packed together in teeming cities to find work, they also feared the new epidemics of their day, even as the devastation wrecked by the Black Death finally began to ebb, with the last fearsome outbreak in 1894. These new plagues on mankind virulently flared up in the increasingly confined quarters of the new urban life, threatening to return people to those harrowing times.

And not only did epidemics threaten the poor and the immigrants, but also the nouveau riche and those born to high society. For contagion did not respect the boundary lines that divided the classes.

Each year as spring gave way to the heat of summer, the fear of yellow fever returned, and, in 1838, cholera, a new scourge, which brought diarrhea, vomiting, leg cramps and death, made its way from India to America. In those days, moreover, obituaries read by contemporaries were not content to recount the accomplishments of the prominent members of society who had succumbed to cholera.

Morbidly, to sell papers, they lavished great attention on the deceased’s last excruciating hours on earth in a manner certain to spread fear through the monied class, who had thought their wealth could insulate them from the vagaries of life. “[He was] struck with sever[e] cramps,” ran the obituary on James Reyburn, a 55-year-old Wall Street lawyer, “passed through the stage of violent vomiting and diarrhea that wring from the victim a thin white, rice water, discharge.” And, the piece continued – “[h]is pulse had weakened to imperceptibility, and his skin had turned the cold, wrinkled blue that marks that final collapse, his physician covered his body with hot salt in a desperate attempt to stimulate is peripheral circulation and restore some sign of vitality [before he finally] died that night.”

That raw fear and helpless dread soon became inextricably associated in the popular mind with the “miasma” thought to emanate out of the garbage that clogged the streets – this being decades before germ theory took hold in the more subtle understanding of how disease actually spread.

Foul and rotting garbage was everywhere in the streets because, from prehistoric times to the closing decades of the 19th century, people continued to toss their slop out the window. Added to the mounds of manure left on the streets in those days of horse and buggies, the trash was picked at by roving bands of dogs and pigs, and rummaged through by rag pickers.

Newspapers and magazines read by the privileged regularly thundered over the fetid and putrid state of the city’s thoroughfares that everyone saw all around them, calling the streets “perfect avenues of swill” and “uninviting pools of filth.”

That sense of primal repugnance by the elites to the streets that they had to cross every day impelled the formation of the Sanitation Movement, which first led to the establishment of carters to collect garbage from homes and stores, and to haul the trash to the outskirts of town. There was just dumped, out of sight, into remote ravines, swamps or gravel pits.

Later, as urban sprawl’s spread out to once remote byways, a litany of leaking dumps and contaminated drinking water, culminating in 1978 at Love Canal near Niagara Falls, led to sanitary landfills and eventually, in 1991, minimum federal landfill standards.

Ironically, it was the founder of the largest waste disposal company who saw this new regulatory burden as an opportunity to exploit. But first, a bit more to explain how it was outsiders who began to convert mundane trash collection into a vehicle for extortion.

Guns. After prohibition was repealed in 1933, the mob needed another line of business to replace booze so it could continue extorting shopkeepers. They quickly swooped in and took over the trash business in many of our big cities; which in New York, the Antastasia and later the Genovese and Gambino crime families went on to operate as a protection racket, overcharging two, three or four times the previous going rates.

“We ain’t giving people no breaks,” Frank Giovinco, the head of the syndicate’s trade association, was recorded boasting about a competitor’s garbage truck that he had two goons torch the night before, back on a warm night in May of 1992. “We ain’t going to let the customers get off the hook. No. It don’t happen.”

The curtain covering up the mob’s secrets had been yanked back when it tried to muscle another tough Italian, unrelated to the mafia, who would not be cowed, and instead talked to prosecutors, telling them, “I won’t be intimidated.”

Salvatore Benedetto’s father and grandfather had moved on up from a horse drawn rag picking cart into a red brick building just north of the Manhattan Bridge to form Chambers Paper Fibers Recycling. Having come up the hard way, he had the temerity to bid for a contract to pick up from 1 Wall Street, a building the wise guys considered to be the family’s property right to service. Mafia-run Barretti Carting had charged the building $9,400 a month. Chambers offered to do the job for $3,900 a month and won the bid.

Furious, Giovinco summoned Salvatore to one of the mob’s favorite watering holes, Giando’s Restaurant in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in order to make good to Barretti by paying him for his lost customer $324,000, which was 40 times what Barretti had pulled out of the building. To make sure that Salvatore understood who he was dealing with, as he got out of his car, he was attacked and punched in the stomach and, for good measure, choked to an inch of his life by a thug Barretti brought along. After Salvatore struggled to his feet gasping for air, Barretti warned him, “You’ll have a lot more problems down the road if you don't return my customer.” The next month, another mob run company who was losing customers to Chambers had two hoodlums beat one of Salvatore’s drivers nearly to death with a baseball bat.

But, through it all, Salvatore didn’t flinch, and, in the end, based on taps from the wire he and an undercover cop wore at great personal risk, 15 defendants from 21 companies and 4 trade associations were convicted. To keep the mob out of the trash industry for good, under the next New York mayor, Rudy Giuliani, set up a Trade Waste Commission to only license new haulers with no mob connections.

As a penultimate footnote, among the tenants of 1 Wall Street, where the prosecutors’ takedown began, was HBO Studios, whose producers had a front-row seat watching the drama unfold, out of which the hit series, The Sopranos, was born.

About the same time that New York’s Commission was being formed, a new student center was being christened in Minnesota as Buntrock Commons at St. Olaf’s college, where newly minted benefactor, Dean Buntrock, had attended. Afterwards, he had entered the garbage business, and navigated its transition from mobs to monopolies.

About the same time that New York’s Commission was being formed, a new student center was being christened in Minnesota as Buntrock Commons at St. Olaf’s college, where newly minted benefactor, Dean Buntrock, had attended. Afterwards, he had entered the garbage business, and navigated its transition from mobs to monopolies.

Raised in a small farming town in South Dakota, Buntrock had outsized ambitions, and, in 1956 he took over a small carting company with just 12 trucks, Ace Scavenging, from his recently deceased father-in-law.

By 1968, he had graduated to the big time in an industry where violence was used to enforce collusion, and he had to be enjoined by Wisconsin’s Attorney General from knee capping uncooperative independent haulers in Milwaukee.

But that speed bump on the path to market power didn’t set Buntrock back. He soon after merged operations with his cousin, Wayne Huizenga and his Florida hauling company, and they took their new corporation, Waste Management, public. They then used their new stock to finance rolling up the waste industry across the country with hundreds of acquisitions a year subsumed into a national behemoth. They also used cartels and threats of retaliation to independent haulers in order to enforce monopoly rents.

However, like the closing of the once Wild West, a private antitrust lawsuit called Cumberland Farms that was handed down in 1988, which imposed a $50 million judgment against the waste giants, made the old ways obsolete. A new business model was needed to keep prices high.

That is when Buntrock had his epiphany. Uniquely, he foresaw that the outgrowth of the Sanitation Movement would soon shutter the small, unregulated open dumps and leave the disposal field to the well-capitalized national firms who could afford costly liners. He envisioned that if he and other waste giants controlled the new generation of expensive landfills, and combined them with their hauling operations into “hubs and spokes,” he could price squeeze independent haulers at day’s end when they had to dump.

As long as the demand for disposal space remained greater than the supply, his plan had the potential to create market power. But, events, centered on those humble peels, conspired to prevent that.

Peels. The first event was the Mobro garbage barge that drove the re-birth of the recycling movement. By creating the perception of landfill crisis, alternatives like diversion were aggressively pursued. Curbside separation of bottles, cans and newspapers ramped up from less than 1,000 to more than 8,000 programs by the early 1990s, which diverted about 30 percent of waste generation from landfills.

By the early 2000s, recycling combined with secular trends like e-books and papers to reduce landfill tonnages even further, and delay the day when supply would tighten. That made Buntrock’s strategy tenuous, but still possible if he could convince investors to hang on for a long slog into the uncertain future.

The next thing that happened was that the urgency for climate action mounted, as concerns became manifest that society was on the precipice of crossing irreversible points of no return. That wound up putting enormous pressure on landfills, which are a major source of methane, to the point that they look likely to become obsolete in their present form. For in 2007 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded that gas collection systems are inherently ineffective and about 80 percent of the methane escapes.

The focus has now turned on keeping our discards that decompose and generate methane out of landfills in order to prevent the greenhouse gas from being produced in the first instance. Diversion of food scraps, along with yard trimming landfill bans, is becoming more and more prevalent.

When we did a survey for the Environmental Protection Agency in 2008, there were already 66 new residential food scrap programs in the United States. By 2013, just five years later, BioCycle found that food programs had tripled to 183. States are also getting into the action, with Massachusetts and Connecticut moving on commercial food scraps, and Vermont on both sectors.

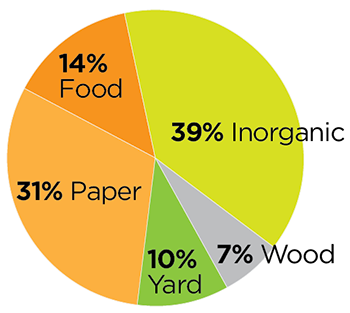

Because those organic discards constitute about 60 percent of waste generation, and landfilled wastes are trending to less than 30 percent of the remaining discards, Dean Buntrock’s hub and spoke business model is rapidly unraveling as supply swamps demand.

Ultimately, it has been the simple fact that, when buried in the ground, the lowly peels from our food scraps create uncontrollable greenhouse gases that has led his “best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men, to gang aft a-gley.”

Like those few Conquistadors of old, little scraps and peels are on the verge of bringing down low a once mighty $22 billion corporation, and leaving it “nought but grief an’ pain, for [Dean Buntrock’s] promised joy.”

About the Author

You May Also Like