College Football Stadiums Tackle Waste

Colleges and universities are utilizing better waste management practices at their football stadiums, with some striving toward zero waste.

Fall brings people together. Every Saturday across the nation, millions of people participate in a time-honored American tradition: college football gameday.

To reduce waste generated during football games, colleges and universities have started to tackle better waste management practices in their football stadiums, with some hoping to close the loop completely by going zero waste.

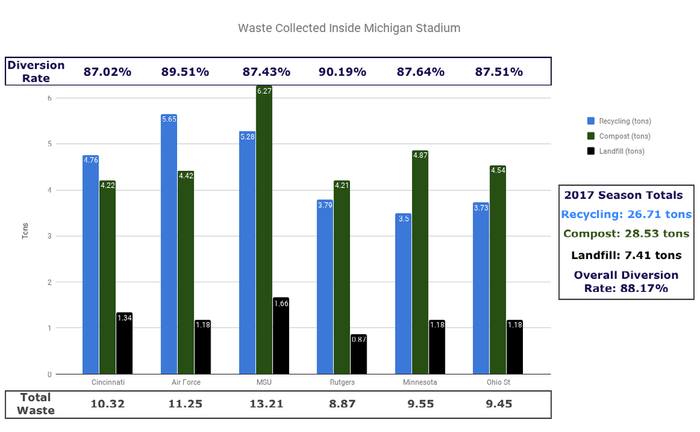

At the University of Michigan in 2017, during the first season of implementation of its zero waste strategy at Michigan Stadium (aka The Big House), the university averaged an 88 percent diversion rate, with waste being diverted to compost and recycling. With seating capacity of 107,601, The Big House is the largest football stadium in the country.

In 2016, the Michigan Athletic Department used the football season as a pilot for its zero waste program and refined operations and concessions. The concession vendor’s contract was updated with specific zero waste compliance language, and while specific materials have not been banned, the vendor and athletic department have worked together to find compostable and recyclable alternatives where necessary.

The program went live in 2017. New signage indicating proper disposal, new compost bins and more recycling bins were the keys to successful implementation.

“We previously didn’t have any signage. We probably had half the number of recycling bins than we had of the landfill bins,” says Paul Dunlop, senior facility manager at Michigan Stadium-Crisler Center, who works in the University of Michigan Athletic Department.

They do not post staff at the bins; therefore, compliance is left up the fans. For the most part, that works. “We are fortunate that our local facilities, our local recycling MRF [materials recovery facility] and our local compost facility have had the ability to deal with some of the contamination that is ending up in there,” says Dunlop. Composting goes to a local facility that is owned by the city of Ann Arbor and operated by a third party.

On Sunday mornings, hundreds of volunteers from a local Ann Arbor high school help with stadium cleanup. The volunteers are trained onsite and guided by images on the stadium’s video boards that illustrate what is compostable and what is recyclable.

During the 2017 season, the university reached the industry standard for zero waste by achieving a more than 90 percent diversion rate during the Rutgers game. For the rest of the season, it hovered just below the mark. In 2017, the program recycled nearly 27 tons, composted more than 28 tons and sent more than 7 tons to the landfill. The diversion rate is calculated with waste collected inside the stadium fence and excludes outside lots and other adjacent areas.

“There are quite a few stadiums engaged in zero waste across collegiate or professional sports. I feel like there are more and more doing it every year,” says Dunlop, who points to Ohio State University as a leader in the field. “It is gaining more traction.”

This is the fifth season for Duke University’s Zero Waste Game Day program, which is organized by Sustainable Duke and Duke Facilities Management and led by Duke Athletics. During the 2015 season, Duke became the first school in the Atlantic Coast Conference to achieve a zero waste football gameday with a 94 percent diversion rate during its game against the University of Pittsburgh at Wallace Wade Stadium (capacity 40,000).

Before the game, student volunteers from Duke and local high school students engage with tailgaters, offer instructions and hand out zero waste rolls that contain a garbage, compost and recycling bag and a zero waste pamphlet. The pamphlets are signed by Duke football players, who prepared 10,000 of the rolls themselves.

Many of the regular tailgaters know the drill and even help themselves to the bags before the volunteers show up for the day. “Building that kind of institutional knowledge amongst visitors and families who come to Duke is awesome,” says Rebecca Hoeffler, communications coordinator for Sustainable Duke.

Inside the stadium, paid staff manage the waste stations and encourage compliance with proper disposal. At concessions, compostable cups and silverware and recyclable materials have become the norm, and there is a ban on Styrofoam and bleached napkins at the stadium.

A third-party contactor starts sorting at kick-off, and Morgan Bachman, recycling and waste reduction coordinator, and her team roll up their sleeves and sort after every game. The post-game sort is extensive and includes waste collected from inside the stadium, tailgating areas and university-sponsored gameday events.

“We really focus on keeping our compost stream as pristine as possible,” says Bachman. “We have very limited outlets for our compostable materials in Durham, and the vendor that we work with is, rightly so, very particular about the material that they accept, so we really have to focus on the quality of that stream.”

The goal is to keep improving. “The progress that has been made, honestly, is more important than hitting 90 percent,” says Hoeffler. “We are getting consistent numbers of upper 70 percent, 85 percent, but what really matters is that now we have built this culture.”

Zero waste is now part of the game plan. “This is not something that is going to go away from Duke football. It is something that the fans are expecting,” says Hoeffler.

About the Author

You May Also Like