Take Me Out of the Waste Stream: Sustainability in Sports

Professional and collegiate sports organizations and athletic facilities are leading the drive toward sustainability, with waste services firms often earning the assist.

The recyclable components of the waste stream discussed in this article are somewhat unconventional: Paper, plastics, cans, peanuts, crackerjack…

Recycling at sports stadiums and arenas has become a key component of most teams’ game plan. And in most cases, waste and recycling companies are essential players in that strategy.

The New York-based Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) earlier this year issued a report, “Game Changer: How the Sports Industry is Saving the Environment.” It praised professional sports for being a cultural leader in the environmental movement.

“In a cultural shift of historic proportions, the sports industry is now using its influence to advance ecological stewardship,” says the report’s executive summary. “At the same time, the sports greening movement has brought important environmental messages to millions of fans worldwide. Sport is a great unifier.”

And recycling is a huge part of that, says Allen Hershkowitz, senior scientist and director of the Sports Greening Project for the NRDC. He says of the 126 pro teams more than half have recycling initiatives. “Recycling is the most visible component of any team’s green project. It’s where fans interact with environmental policy. They don’t see energy, but they see the recycling programs.”

And recycling is a huge part of that, says Allen Hershkowitz, senior scientist and director of the Sports Greening Project for the NRDC. He says of the 126 pro teams more than half have recycling initiatives. “Recycling is the most visible component of any team’s green project. It’s where fans interact with environmental policy. They don’t see energy, but they see the recycling programs.”

Customer expectations grow as a result, both for the team and for the recycling service providers it hires. “They’re educated on recycling, how it’s the right thing to do,” says James Saxe, director, field sales for Phoenix-based Republic Services Inc. “The fan base is starting to demand it. The key is that you have to make it convenient for them to do it.”

Cincinnati-based Rumpke Consolidated Companies Inc. works with their hometown Major League Baseball club, the Reds, who want to have the greenest ballpark in America, says Amanda Pratt, Rumpke’s director of corporate communications. Her department is actively involved with the Rumpke’s recycling operations because “it won’t be successful unless you have education and promotion tied to it.”

The Reds have about 150 recycling containers spread around the ballpark and throughout their corporate offices. The team operates its own cardboard compactors. There’s a facility management Green Team trained to empty the containers and get recyclables directed to the right place. The team is augmented by the Green Guardians, about 25 volunteers who, during weekend and big-attraction games, go through the stands during the seventh-inning stretch to collect bottles and cans for recycling. A video message starring Reds rightfielder Jay Bruce shown during the game reminds fans to recycle. Bruce does radio ads for recycling on the Reds Radio Network as well.

Mascots and Baseball Cards

The Green Guardians help out the minor league Dayton (Ohio) Dragons and Louisville (Kentucky) Bats as well. But Rumpke will add other twists, such as a Fan Zone day that features a recycling truck fans can check out, Binny the Rumpke Recycling Bin mascot, and baseball cards with recycling statistics and instructions.

Rumpke’s efforts also extend to other sports. The company provides special recycling containers in tailgate areas around Paul Brown Stadium, home to the National Football League’s (NFL) Cincinnati Bengals. Local Xavier University has student volunteers collecting bottles and cans for recycling, as well as a series of recycling service announcements featuring the school’s football coach. The minor league Cyclones hockey team hosts trivia questions on recycling during the game written by Rumpke. And Rumpke has just started a program with giant Ohio State University in Columbus.

“Such a big part is the public awareness issue with all the venues,” Pratt says. “We want to promote the right way to recycle no matter where you are. It’s a platform to further that message.”

“Such a big part is the public awareness issue with all the venues,” Pratt says. “We want to promote the right way to recycle no matter where you are. It’s a platform to further that message.”

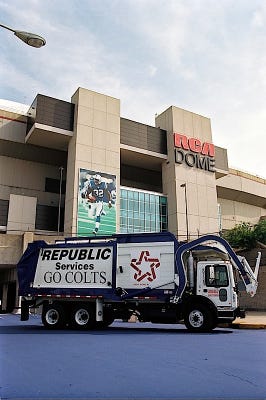

Republic also does Green Team volunteer recyclables collections with MLB’s Kansas City Royals. This year the company added 100 recycling-only containers at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington, Texas (home to MLB’s Texas Rangers), and will add another 100 next year. The NFL’s Indianapolis Colts and the NHL’s Nashville Predators are customers. The NBA’s Portland Trailblazers’ Rose Garden is one of the few sports facilities to achieve LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Gold certification; Republic works with the team to design recycling stations, do composting, help back-of-the-house staff and provide monthly diversion reports.

“When people have a choice to make with recycling they generally make the right choice,” Saxe says. “We want to give them the opportunity.”

Sports facilities want help from waste and recycling companies. “They are looking for people to come in and partner with them to provide those solutions,” Saxe says. “If we can help them reduce their waste through diversion or other ideas then we certainly want to do that. There’s a whole lot we do other than just picking up the waste. What’s the best way the waste gets from point A to point B (the dock)?”

Rumpke approaches each sports team customer with an open mind. “We customize how to best meets needs of the waste stream,” Pratt says. “The Reds were looking for ways to increase sustainability. Other groups may need to have it explained why it’s beneficial to them.” But those organizations quickly see the benefit once educated, she says.

And Rumpke feels it’s at no disadvantage competing against the larger waste and recycling companies. “We feel we’re just as prepared if not more prepared than our competitors,” Pratt says.

Cleveland Recycling Rocks

At Progressive Field, home of MLB’s Cleveland Indians, the organization had recycled for a time. Brad Mohr left the organization and came back five years later in 2005 as assistant director of ballpark operations. He noticed that the ballpark recycling bins were gone and its commingled recycling compactor kept getting contaminated. “There’s got to be a better way of doing this,’” he says he thought at the time. He talked to a lot of people and decided separating recyclables on site was the way to go.

Mohr contracted with Gateway Products Recycling Inc. of Cleveland and bought a baler each for plastic bottles and for cardboard. Between the commodity sales and the cancelled waste hauling the change generated $30,000 the first season, and the team paid off the balers in six months.

“That got a lot of attention, and the team told us, ‘What else can you can do? Go do some more.’” Mohr expanded recycling efforts to include bulks and ballasts, food and electronics. Some of the food is composted and some is donated to a local food bank. Mohr says the team also has gotten smarter about food preparation.

“That got a lot of attention, and the team told us, ‘What else can you can do? Go do some more.’” Mohr expanded recycling efforts to include bulks and ballasts, food and electronics. Some of the food is composted and some is donated to a local food bank. Mohr says the team also has gotten smarter about food preparation.

In 2011 Progressive Field, home to the Indians, had a diversion rate of 22 percent (195 tons out of 682 generated), which has steadily increased since the 13-percent total in 2008. “I know we can get that a lot higher if we can find a way to get more food waste composted,” he says. Mohr is particularly proud though that in 2011 Progressive Field fell below an average of one pound of waste generated per fan (0.84 pound).

Mohr says the team now saves $35,000 to $50,000 each year from reduced trash disposal. “It’s not only doing the right thing, but we can make some money on this.”

At Progressive Field the recycling bins used to be emptied every three days; now they’re serviced after every game because they fill up so fast, Mohr says. And stadiums are giant venues: Progressive Field covers 1.2 million square feet. “To capture as much as we do is great,” Mohr says. “We’re not going to be perfect. That’s ok. I know we’re doing something right.”

At Progressive Field the recycling bins used to be emptied every three days; now they’re serviced after every game because they fill up so fast, Mohr says. And stadiums are giant venues: Progressive Field covers 1.2 million square feet. “To capture as much as we do is great,” Mohr says. “We’re not going to be perfect. That’s ok. I know we’re doing something right.”

Republic also does recycling for the team, and Mohr says both service companies have been key to the team’s success. Republic had been collecting aluminum for recycling along with the ballpark’s waste. The company convinced Mohr that it had improved its single-stream recycling separation, so now Republic recycles Progressive’s plastic together with its aluminum.

Given their on-the-field competitiveness, it’s understandable that the teams are similarly competitive about recycling, trying to outdo each other in terms of diverted waste volumes and sustainable innovations. But they also share ideas. Mohr says he takes part in regular weekly sustainability meetings with other stadium managers around the league to compare notes.

Minor League, Major Diversion

Rumpke partnered with the Dayton Dragons, the single-A farm team of the Reds, a couple of years ago. The company helped the team implement many of the same techniques the Reds are employing, albeit on a smaller scale. It also worked with the Dragons’ catering and concession company. The result has been a 38-percent diversion rate of the 121.8 tons generated at their ballpark in 2011. The team saved more than $2,000 in disposal fees in 2012, Rumpke says.

The only difference between the minor leagues and the majors is the scale of the crowds and games, says Brad Eaton, vice president of sponsorship services for the team. The team’s stadium has a stated capacity of 7,250 and it hosts 70 home games over the course of a season. But the Dragons have been averaging 8,500 fans per game, with 913 consecutive sellouts.

The only difference between the minor leagues and the majors is the scale of the crowds and games, says Brad Eaton, vice president of sponsorship services for the team. The team’s stadium has a stated capacity of 7,250 and it hosts 70 home games over the course of a season. But the Dragons have been averaging 8,500 fans per game, with 913 consecutive sellouts.

Mohr says recycling has become part of the internal culture at Progressive Field, and the fans expect it. But he also realizes it’s a balancing act. “Fans come here to be entertained,” he says. “It’s a fine line to tell our fans you need to put this in this bin, this in that bin. We need to have that engagement for those who seek it but we don’t want to be in your face with it.”

Not only do sports facilities have a transient customer base, but the crowds can vary widely from day to day, sometimes with very short notice. “You have to be accommodating to those fluctuations and be on call 24 hours a day be able to make adjustments,” Pratt says. Saxe adds that quick turnaround between events can be necessary. “You can have a ballgame go until 11 o’clock one night and then start at noon the next day. “It’s important that you form a good relationship with staff and you get the buy-in because you have to work in conjunction with each other.” Also, events and customers can vary widely at stadiums and arenas, from sports to concerts to tractor pulls to Disney on Ice.

Contamination is a much greater challenge with sports facilities, Pratt says. Food waste and paper products pose problems; amber beer bottles are a more challenging plastic to process. “The stuff is not as great as what we get out of a typical curbside or commercial recycling,” she says. “But if you have the material recovery technology in place, it can be dealt with.”

Container design is also vital in a sports venue, says Steve Sargent, Rumpke director of recycling. A properly designed bin can optimize participation while minimizing contamination, ensuring that the correct items find their way into the bins more easily.

Different Playing Fields

Hershkowitz says while sports teams have generally embraced recycling, the recycling infrastructure in the United States remains underdeveloped, and that lack of development can lead to significant regional differences in recycling success. Moreover, the playing field isn’t level because landfilling and incineration get subsidies recycling doesn’t, he charges. “Finding environmentally preferable products at competitive costs is a challenge, and it can’t be achieved overnight.”

David Scott is president of the Stadium Managers Association as well as general Manager & Race Director of Miami-based U.S. Road Sports & Entertainment Group of Florida LLC, which manages running events. The association represents most of the MLB clubs, NFL teams and Major League Soccer. While he has seen the transformation of sports facility operators in tandem with the rise of environmentalism, coming a long way from when he was game administrator for the Orange Bowl in Miami, he notes that economics still is a factor. “Sometimes it can be more expensive for a facility to take it on and not get return from it. Then it becomes an ethical philosophy,” he says.

Hershkowitz acknowledges that for sports organizations it’s a mixture of self-interest and altruism, starting with the commissioners of the leagues. “You don’t get this job by being ignorant of social issues,” he says. The same is true for waste and recycling companies, which he agrees play a vital role in the greening of sports. But it’s good visibility for the companies as well.

Hershkowitz acknowledges that for sports organizations it’s a mixture of self-interest and altruism, starting with the commissioners of the leagues. “You don’t get this job by being ignorant of social issues,” he says. The same is true for waste and recycling companies, which he agrees play a vital role in the greening of sports. But it’s good visibility for the companies as well.

Sports venues are an attractive market for Republic, Saxe says. “Anytime you can reach a mass audience – all these people have homes. If we can touch them at a sporting event and they see we offer this product it could potentially help us from a commercial and even residential standpoint,” he says.

Sports’ extraordinary visibility and impact extends to its supply chain, which is one of the biggest on the planet. For teams to request environmental products is huge, Hershkowitz says.

Recycling and environmental initiatives have become a priority for all professional sports, but MLB makes the biggest impact just from its volume of events, Mohr says. It also benefits from being a family-oriented summer event. Kids often point out to parents the nearest recycling bin or an adjacent wind turbine.

Educating Higher Education

Scott says college sports lag well behind the professionals. The economy is one factor. The Stadium Managers Association has only 25 of the 121 potential Division 1 football schools as members.

But a bigger hurdle for college facilities, Hershkowitz says, is that the facilities are not controlled by the athletic departments but by the university overall, so the savings don’t go directly to the teams. The NRDC is hoping to focus on colleges, furthering their recycling and environmental efforts at sports facilities in the future. “On the other hand,” he says, “there are opportunities because students and administrators understand the need to advance environmental stewardship. We don’t have to convince them.”

But a bigger hurdle for college facilities, Hershkowitz says, is that the facilities are not controlled by the athletic departments but by the university overall, so the savings don’t go directly to the teams. The NRDC is hoping to focus on colleges, furthering their recycling and environmental efforts at sports facilities in the future. “On the other hand,” he says, “there are opportunities because students and administrators understand the need to advance environmental stewardship. We don’t have to convince them.”

And sports provide a unique opportunity to make the sustainability argument. Change isn’t brought about by government, it’s brought about by people, Hershkowitz says. “We need a cultural shift in the way Americans view their relationship with the environment.” Sports offers a populist means toward that end, he says. “The environment often has been politicized. Having pro sports embracing environmental stewardship takes the politics out of it and creates a dialogue in an incredibly valuable way.”

The recycling push at sports facilities will only increase in the future, Pratt says. “It’ll become almost a negative to not be into recycling. And as technology improves we’ll find better ways to handle this.”

Mohr’s goal is simply to get the diversion rate higher. “Food waste collection is key to that.” Teams with a weaker recycling record can catch up, he says. “If you are a team that hasn’t started, call one of the ballparks. You have your map on where you need to go. The tough work has been done.”

There’s still a lot to do, Hershkowitz says. A lot of teams still need help. And a lot of fans will be watching. “Billions of people follow sports. Teams can use that platform to get a message out in an incredibly effective way.”

Allan Gerlat is News Editor for Waste Age and waste360.com.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)